Teaching with Humanities for All (Even Online!)

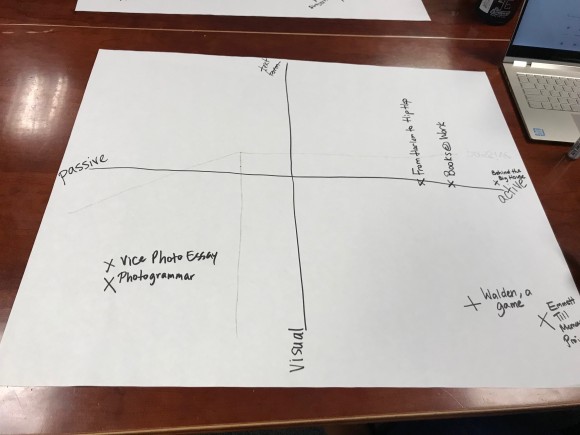

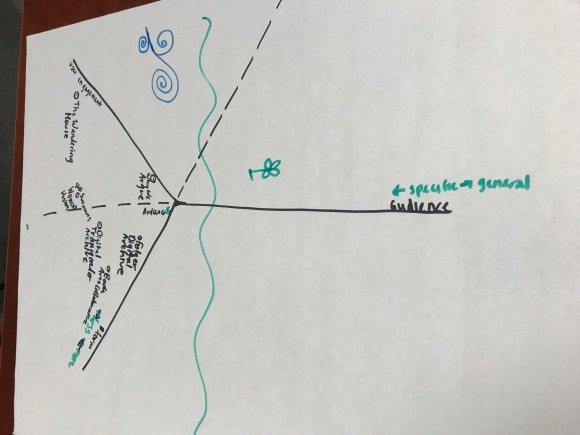

Students mapping projects from Humanities for All. Image courtesy of Matthew Pavesich.

Note: What a time to be alive: I drafted most of this blog post before March 2020, and then the world turned upside down. The pandemic necessitated online instruction at a scale that must have shocked even the most ardent MOOC supporter. Simultaneously, convulsive and grief-fueled racial upheaval emerged all across the world in response to the murder of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and others. Universities and the humanities have always been both a part of the problem and a part of the solution: they are entangled in racism and they persist as sites of transformative opportunity. To me, the public humanities especially hold potential for radically transformative work. And everything that we can do, from our teaching positions of power, to work with students as they acquire the means and methods to change the world (they already have the motivation!), helps to tip the scales.

This post is about one simple classroom exercise with the Humanities for All database, which works both online and F2F. But first let’s zoom way out in order to zoom back in.

Zoom Out

Some say—and have been saying for decades—that the humanities are in crisis. In optimistic moments, I prefer to think that we’re in a moment of evolutionary adaptation, changing who we are and what we do in response to significant pressures of all sorts (economic, political, cultural, and more).

In navigating this complex context, there are many ways to advocate for the humanities. The National Humanities Alliance (NHA) engages in several of them, including legislative advocacy, convening stakeholders, and documenting, promoting, and building capacity for innovative humanities work. NHA’s Humanities for All, for example, collects examples of publicly engaged humanities work including research, teaching, preservation, and public programming. Much of this work considers how to broaden the audiences for and expand the forms of the work. I’ve engaged in public humanities work myself, and I continue to think about and work on the ways I can integrate my research and teaching interests with public action.

For those of us in teaching positions, I’d suggest that we should consider our classrooms to be places for students to become attuned to what the humanities are becoming. Our classrooms, that is, can become laboratories where we collaboratively think, see, and feel our way into more expansive, generous, and vibrant versions of what the humanities are and can be in the 21st century. Crisis, if that’s what this is, might be an opportunity.

Zoom In

There are all kinds of ways to integrate public and engaged humanities work into our classrooms, but I’ve had the good fortune to be able to develop an entire course devoted to the public and engaged humanities at Georgetown University. In my English 434: Humanities@Work class, we ask two big questions: (1) what can the humanities do in public (culturally, politically, economically, etc.), and (2) what can we, as individuals with training in the humanities, do in the world (professionally, civically, personally, etc.)? The goal of the course is for students to come away with a broader sense of what the humanities are, what they achieve, and what they are good for—and for students to see a more expansive horizon in which they can work and grow. The exercise I describe here is one that I situate near the start of the semester in Humanities@Work.

The biggest challenge in a public humanities class is that we’re usually starting from scratch. It’s the rare student who already has a good sense of what the “public humanities” are, let alone a sense of the range of work or the possibilities therein. I can assign all the reading in the world, but that’s not enough for students to get a sense of the rhythms and flows of public engagement. We need to examine public humanities projects—lots of them—for students to see what exactly this kind of work can be. Humanities for All offers a perfect resource for this purpose.

During the first week of class, I ask students to explore the Humanities for All database and to come to class having identified three publicly engaged humanities projects that especially caught their interest. I also assign the NHA’s accompanying essays on the goals and types of publicly engaged humanities work. In small groups, students discuss the three projects that caught their eye, using the accompanying essays to consider ways to analyze the projects. This conversation helps all students become familiar with a number of projects, while also asking them to look at them in relation to each other.

Next, I ask students to map all these projects in relation to each other on axes that they identify as relevant. These axes can be of a wide variety: size or specificity of audience, emphasis on the textual and/or the visual, the design for instruction or interaction, and (infinitely) more. The point is to engage students in even more active variations of the strategic thinking that goes into the composition of such work. Students, at first, are a little bewildered by my request, but once it becomes clear that I’m inviting creative activity, rather than asking for a correct answer, things begin to loosen up and get weird in a good way. Here are a few images of these maps from this last semester:

If teaching online, there are a number of tools one might use to conduct this exercise in a digital synchronous or asynchronous environment. Google’s Jamboard, Canva, Prezi, and other visually-driven platforms allow students to spatially arrange text and images, and that’s all you need. This exercise suffers not at all from a transition online. Each group can present through screenshare in Zoom, if synchronous, and via blog posts on a shared class blog, if asynchronous.

And so, in the space of one brief class activity, we have: (1) familiarized ourselves with a number of public humanities projects, as well as the NHA’s helpful typology and goals for such work, (2) engaged in a reflective exercise that considers the strategies of specific individual projects, and (3) extended that reflection beyond the analysis of individual projects to analyzing projects in relation to each other. This combination of tasks both familiarizes students with the public humanities landscape and invites them to consider these projects from the perspective of those who created them, necessary first steps towards doing this kind of work oneself.

Zoom Back Out

In the current iteration of this class, students go on to analyze other people’s projects in our Precedent Studies assignment, to identify their own values, skills, and goals in a Public Humanist Statement, and to prototype their own public humanities projects. But it all starts with the simple exercise I describe above. The exercise amounts to one small step at the very beginning of a semester, but when things go right it sets in motion everything that follows: an evolution for students that expands their sense of what the humanities make possible for them as individuals and for the world.

As the humanities evolve into something that none of us quite has a handle on yet, it seems crucial to involve students in the work of re-creating the humanities, especially insofar as it becomes a partnership among an increasingly diverse group of people and institutions. If we’re becoming something new, best that it be driven by humanists of all generations with as wide a view on the work as possible.

Matthew Pavesich is Teaching Professor of English and Associate Director of the Writing Program at Georgetown University. His publicly engaged rhetoric project on how Washington, DC residents visually remix their flag, DC/Adapters, can be found in Humanities for All and online.

Learn how to contribute to the Humanities for All blog here.