CETA Murals Remembered: At the Intersection of Public Art and Public History

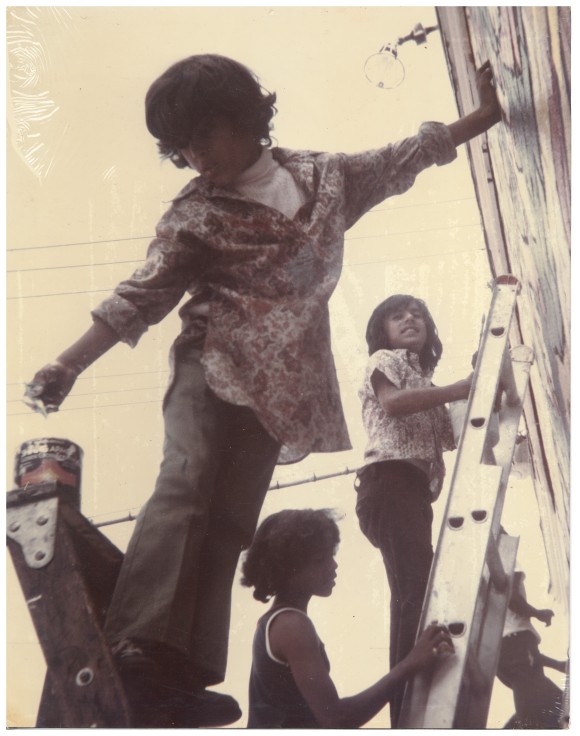

Togetherness, mural painted on the corner of Ivy and Newhall Streets, New Haven, CT, 1976. CETA Youth Summer Program Participants led by Terry Lennox. Image courtesy of Ruth Resnick Johnson.

Street Scene: CETA Murals, New Haven, and the Late 1970s is a new digital exhibit created by Lori Goldstein and Alison Verplaeste of the Public Art Archive using materials digitized and curated by Laura A. Macaluso. Crossing disciplinary boundaries between public art and public history, the exhibit showcases the local application of a national program called the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act, or CETA, legislated by Congress in 1973. With CETA federal funds, municipalities across the country were directed to offer a jobs-to-work program, but how each community pursued that goal was open-ended. Incredibly, like the Works Progress Administration (WPA) of forty years before, the arts—including visual, musical, theatrical, culinary arts, and more—were welcomed within the CETA framework and many communities, from Los Angeles to Minneapolis to New Haven, put the funds to use by hiring emerging artists.

The Street Scene exhibit demonstrates the remarkable results of CETA funding in New Haven, Connecticut. The last remaining CETA murals were still visible until the 2010s, when redevelopment of buildings destroyed the ghostly imprints of the original brightly colored murals. In this exhibit, seventeen murals were resurrected using digitization and mapping. The opportunity to revisit the forgotten mural program was possible because one of the original CETA artists, Ruth Resnick Johnson, had kept hold of her personal archive of photographic images and archival materials for more than thirty years. Using a digital platform to create this exhibit enabled a more holistic view of the workings of the program and its impact, beyond what previous print-based scholarship could offer. Mapping allowed us, for the first time, to “see” where CETA murals were located and to assess their number and placement against New Haven’s other examples of public art. This is possible because the city has utilized the Public Art Archive since 2010, making available hundreds of examples of public art throughout the city through the freely accessible website. Discerning CETA’s unique place in New Haven’s long history of public art making was part of our Street Scene project.

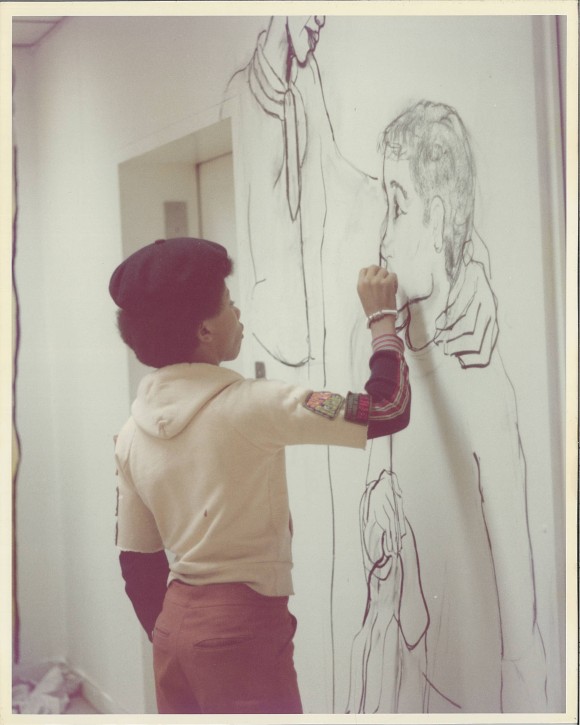

These CETA murals were made by and for communities who had previously been left out of the visual culture of the City of New Haven, including Black, Latino, and the elderly. The CETA murals were purposefully located away from the elite power structure of City Hall and Yale University, entities located downtown around the New Haven Green. Instead, neighborhoods that had previously seen little public art up and close and personal became art-making and identity-making sites of significance. Two murals of note are the Spirit of ‘76 mural, painted on the brick sidewall of a hardware store in the Hill neighborhood with the guidance of the Puerto Rican Youth Services program, and Path of the World, painted on the exterior wall of the Richard C. Lee High School Gymnasium with students from the school. Both of the murals—–done by youthful participants—feature swirls of color, imaginative scenery reflecting both city life and the psychedelic musical culture of the era. A guitar is painted on one wall, and inside Lee High School, the CETA program muralists gave a whole wall over to Stevie Wonder.

Today, New Haven is well known for its community-centered public art making, but the CETA murals were the first. Although there is still more to learn about CETA in New Haven—its successes and limitations, its impact on individual participants and the city—others are doing this work around the country, too. Through the Street Scene exhibit project we connected with the CETA Arts Legacy project, an open and accessible state-by-state resource for documentation co-sponsored by Franklin & Marshall College.

Virginia Maksymowicz and Blaise Tobia have led the CETA Arts Legacy Project for many years, working to document CETA across the country and create and support new exhibits about the now-forgotten program. They are aware that there are many artists and participants who could give oral histories about the impact of CETA on their lives and careers and that the work—fifty years on—should happen before those first-hand testimonies are lost. Maksymowicz often points to the fact that when funding for the arts and artists in regards to employment is mentioned, the WPA is at the top of everyone’s tongue. But CETA deserves this recognition too, as it gave a start to many artists and arts organizations which went on to shape American society through the end of the 20th century.

CETA murals may be gone in a physical sense from the public spaces of New Haven, but they had an important role to play in the 1970s, a decade of economic stagnation, decaying cities, and continuing racial strife and struggle. In New Haven, CETA murals were a meaningful avenue through which the visual arts became a tool for supporting a collective sense of place and an embrace of more diverse visual representation in the public sphere.

Laura A. Macaluso, Ph.D. researches and writes about monuments, murals, material culture and museums. She has a PhD in the Humanities from Salve Regina University in Newport, RI and is the author, editor, or contributor to more than ten books, including The Public Artscape of New Haven: Themes in the Creation of a City Image (2018) and Monument Culture: International Perspectives on the Future of Monuments in a Changing World (2019). More of her work can be found at lauramacaluso.com.