Reimagining the Humanities Center – A Great Experiment

C21 Summer Fellow Jamee Pritchard interviews Alex Hanesakda at the Mobile Story Cart during the Milwaukee Southside Organizing Center Garden Fest. A Nourishing Trust poster from C21's 2022–2023 programming is included with other materials on the back panel of the cart. Image courtesy of Yuchen Zhao.

In 2021, in a rare moment in the 55-year history of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee’s Center for 20th / 21st Century Studies (C21), the Director and the Deputy Director positions turned over at the same time. The turnover, the pandemic, and a slow and unnervingly consistent loss of funding (and colleagues along with it) created a moment for radical reimagining: What is a 21st-century humanities center?

C21 had traditionally offered fellowships (with course release) to focus on research, seed funds for collaborative projects, and a conference on a cutting-edge humanities topic that the staff edited into a book.

The turnover was an opportunity to start anew with principles, processes, and programming that looked toward the uncertain future of both humanities and the university.

It has been two years already. What have we done? What are we learning?

C21’s original charter was prescient.

The original, 1968 charter stated that the complex challenges of contemporary society are best addressed with multiple voices and expertise and that our mission was to build a community of scholars to address the pressing issues of our time.

As a community-engaged scholar/artist, Anne took that to mean community and scholarly expertise. So, the Center would address issues that are lived, felt, and studied deeply by both scholars and community experts. This would be an enormous change for C21, which was internationally renowned for its focus on critical theory but largely unknown in its hometown.

Commit to shared leadership.

Contemporary academia is in flux. Retirements and farewell parties dramatically out-number welcoming events for new faculty at our under-resourced public university. If the Center aimed to establish partnerships and relationships with community organizations and experts, those partners needed to be assured that in two years the Center wouldn’t just drop a given theme, program, or process.

The leadership would need to be built to withstand inevitable transitions. Our leadership team is a Director, a Lead Faculty Advisor (who is presumed to be next in line for directorship), and Deputy Director. We are advised by a council made up of faculty, staff, graduate students, and community experts/leaders. Together (with a wider group of scholarly and community stakeholders), we think about what 21st-century pressing issues we want to focus on for three years at a time, expanding the center’s tradition of yearly themes and annual conferences.

Commit to clear, transparent processes.

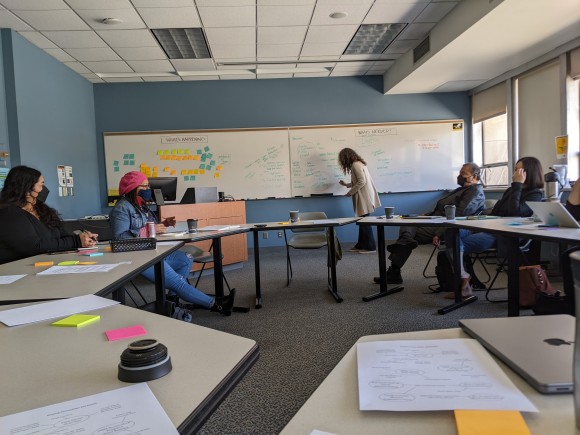

Our leadership team created processes for everything we do, making clear and transparent how we select themes, fellows and speakers, and how we spend our funds. If making a selection matrix was an Olympic event, we would win. It sounds boring, but it has been giddy work (truly, our weekly meetings are filled with laughter). We write the processes on white boards strewn about the office, then on the website. We wrote our budget on the glass walls of the library during an Open House. A clear process template is a shield against sudden transition, and most importantly, transparency is a precondition for equity.

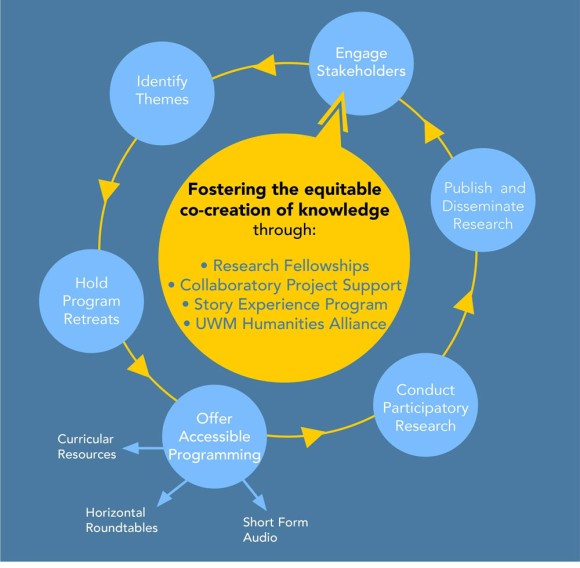

Commit to responsive experimentation (aka learning).

As an interdisciplinary humanities center, we are experimenting to find structures that support the co-creation of knowledge to address the pressing issues of our time. We don’t know what works yet. But we have built a responsive, asset-based process (building on existing strengths) to guide us as we learn, reflect, and respond.

We started our experiment in 2021 with an open survey. We sent it to our existing Center mailing list, and added community leaders and faculty and staff in humanities and humanities adjacent areas of study. We opened the survey, enabling it to be forwarded and shared to anyone. We asked, “What issues are top of heart and mind?” We made the survey open so anyone could answer, requiring only that they share their geographic location (we would give priority to regional responders) and inviting participants to voluntarily share their name and position. We did themed analysis of the responses by reviewing the data and identifying patterns and ideas that emerged. We engaged the Advisory Council to respond to the ideas that emerged. We exercised leadership and created programming themes based on the combination of survey and advisory council response.

Staying open and responsive over time has been a core challenge. Most programming is set months if not a year in advance. How could we create space for the emergence of partnership (community and academic) and the co-creation of knowledge? What forms of programming and publishing (something we had always done) might allow for that? How could we reward participation in the co-creative process equitably—acknowledging that risks and rewards are very different for faculty, staff, students, and community partners? What kind of preparation would people from a range of expertise need to engage in an issue?

We realized that what we were doing was endeavoring to create a humanities center that went beyond “public” and “traditional” humanities divisions. At a public institution with a dual mission of access and excellence in research, our humanities center absolutely needs to be both. The C21 team aims to step into the world that does not distinguish between public and traditional humanities by offering multiple points of access to a given topic, and by honoring multiple ways of knowing and understanding it.

Let the form of programming emerge from the goal.

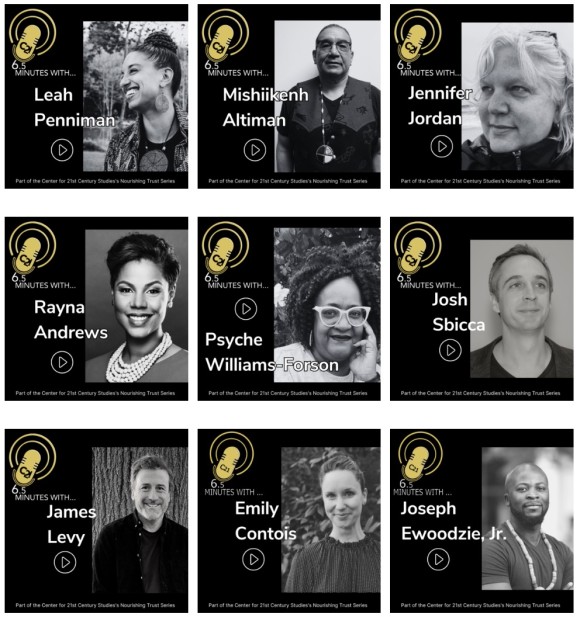

We decided to break open our traditional 2-day “conference” format with a series of events and materials that unfolded over the course of a whole year. Our programming would begin with a series of brief, bi-weekly podcasts—6.5 minutes with C21—interviews with emerging (students or early career) and established academics and community experts on a given topic.

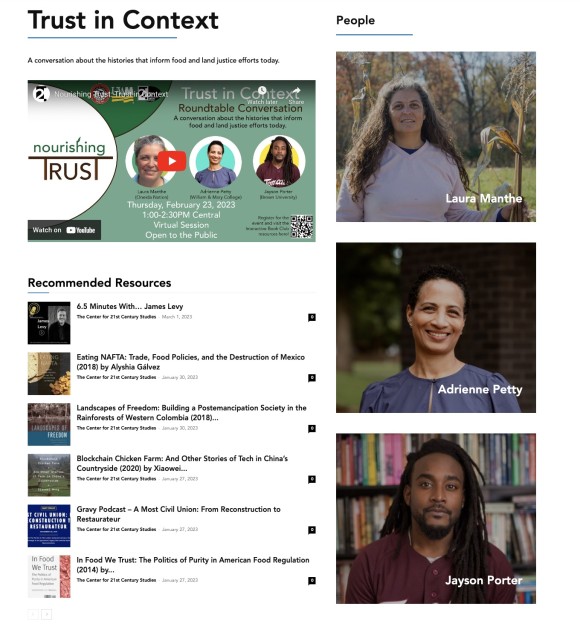

The podcasts would be followed by facilitated roundtable discussions that featured the same spread of experts (emerging, established, and community). The range of expertise keeps the language open, creating space for something new to emerge between and across the fields of practice.

We were thrilled this year to partner with the Milwaukee Turners – a historic club committed to social justice since 1853. The Turners co-hosted the roundtables on Zoom and Facebook Live. Our partners at UWM, the Serious Play Collaboratory, broadcast the roundtable on Twitch. The audience numbers for our three roundtables on Nourishing Trust: Considering How Food and Land Connects Us quadrupled from last year when we hosted our own Zoom panels.

After the roundtables were complete, we sent the transcripts to the participants and additional respondents and asked them to annotate them by adding resources, ideas, and insights that emerged from and after the dialogue.

To support the roundtables, we also created an “interactive book club” which included a list of additional resources (readings, audio, video etc.) that took attendees deeper into the topic.

The final piece of the programming was a sensory/story survey that aimed to gather and present stories inspired by the topic. Our first survey was fully virtual. This year, we commissioned the design and fabrication of a Mobile Story Cart that can go out into the community to invite and honor stories in person. We invite artists to collaborate with us on presenting the story data we gather.

Commit to reimagining the “book”.

After reinventing the programming, we turned to the center’s longstanding publishing tradition—an edited volume with essays from the conference proceedings. The guiding question was similar: what form of publishing could equitably reward the range of participants that we bring together? A traditional academic book is designed to reward the rising scholar with a high-level peer-review publication. But it is often inaccessible and incomprehensible to community experts.

We opted instead for annotated transcripts of the roundtables, which allow all participants to revisit and rethink the conversations, to revise and recommit, to stay or change the course—and to speak to each other so that unexpected exchanges and collaborations can occur over time. These transcripts also complicate the two-way dynamic between academic and community-based forms of knowledge production and challenge the assumptions we might have about how ideas flow easily or linearly between the university and its neighbors. Instead, we explore how knowledge production is horizontal, with concepts, systems, and embodied experiences cross-pollinating each other across varied disciplines, histories, and lived experiences.

Our current puzzle is to find an appropriate publishing venue. Our multi-modal, co-creative publication is still in search of a home. It is a thrilling historical moment as open source and digital publishing takes hold, but frustrating as well for an under-resourced, access-focused public institution.

We commit to learning... and inviting others to join us.

We continue to hold open the learning process, adjusting as we go. Most recently we created a HuMetricsHSS-inspired evaluation of just four aims (with a playful Likert scale: Not at all / Somewhat Lacking / Neutral / Doing Well / Really Good Stuff) for our Advisory Council to review our efforts. These include:

- C21 aims for openness—to be clear, transparent, candid, and learn from mistakes.

- C21 aims to be equitable—centered on the public good, social justice, and accessibility.

- C21 aims for collegiality—to build community with kindness, playfulness, respect, and generosity.

- C21 aims for the highest quality in all we do—in creativity, research methods, and design as we co-create knowledge together.

We invite you to follow our efforts and let us know how we are doing in our continuing experiment.

Anne Basting is Professor of English at UWM and Director of the Center for 21st Century Studies (C21). Her writing and large-scale public performances focus on the creative potential of care relationships and have helped shape an international movement to extend creative and meaningful expression from childhood, where it is expected, through to late life, where it has been too long withheld.

Jennifer Johung is Professor of Art History at UWM and Lead Faculty Advisor at C21. Her most recent work considers new formations and qualifications of life at the intersections of contemporary art, architecture, and biotechnologies. She also curates exhibitions in and beyond Milwaukee.

Nicole Welk-Joerger is the Deputy Director of C21 at UWM. As an interdisciplinary historian with a background in art history, anthropology, and the history of science, her work focuses on changing definitions and practices of health and sustainability. She has long researched these ideas in the history of agriculture and continues to explore them in the context of university systems.