The Displacement Project: Archival Storytelling and the Sisters of the Holy Cross

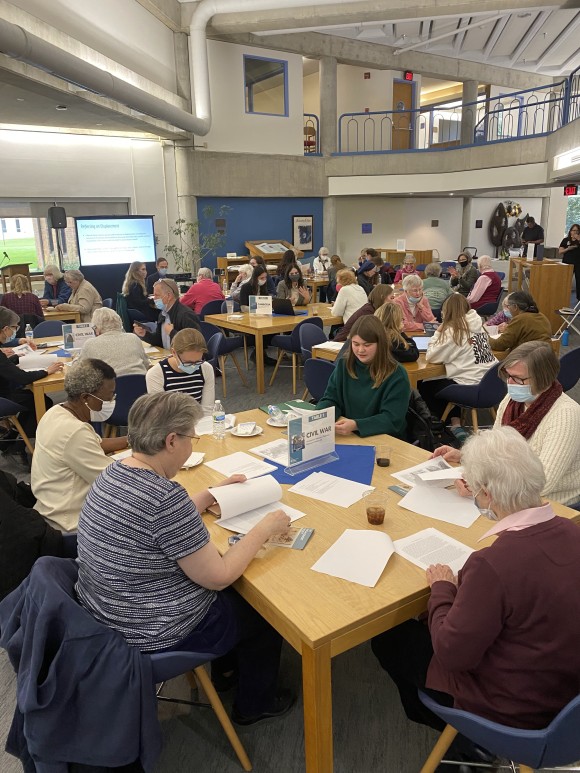

Members of the faculty-student research team: Dr. Jessalynn Bird, Dr. Sarah Noonan, Dr. Laura Williamson, Mary Coleman, Kaitlin Emmett, and Marirose Osborne. Photo courtesy of Michele Marlow.

The campus of Saint Mary’s College (Notre Dame, Indiana) is home to a unique archival collection: the Congregational Archives and Records of the Sisters of the Holy Cross. Among faculty and students at the College as well as in the broader South Bend community, the Sisters of the Holy Cross are widely known for their role in the Saint Mary’s origin story, but their historic (and continued) global relief efforts are much less familiar. As one student reflected, “They founded our college, but the history of them is kind of hidden.” The great irony of this perspective, of course, is that the vibrant, nearly two-hundred-year history of these women religious—and of their action—is housed just a stone’s throw from a popular campus dorm in the sisters’ own carefully curated archive: a gem “hidden” in plain sight. In an effort to amplify the voices and stories of both the Sisters of the Holy Cross as well as the people they served, a research team at Saint Mary’s College embarked on a two-year public humanities project focused on the sisters’ work with refugees and displaced peoples in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

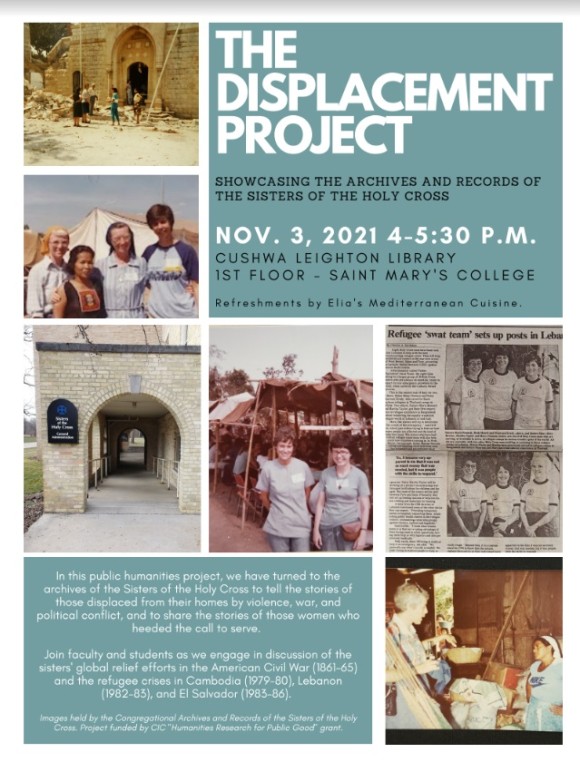

The Displacement Project, as it came to be called, was funded by the Consortium for Independent College’s Humanities Research for Public Good grant (2019-20), which supports publicly engaged archival work focused on issues of community concern. In forming the contours of our project, we were especially animated and emboldened by three things: the ongoing mass displacement of peoples worldwide, the sisters’ long standing commitments to “welcoming,” and the opportunity to bring archival research directly into the hands of undergraduates. In forming our collaborative team, we turned to a group of faculty, students, librarians, and community partners invested in sharing these undertold stories of justice and advocacy. Three faculty (Dr. Jessalynn Bird, Dr. Sarah Noonan, and myself) worked alongside two student research assistants (Mary Coleman and Kaitlin Emmett) from the departments of Humanistic Studies and English for several months, digitizing and researching archival material related to the sisters’ relief efforts during four geopolitical conflicts: the U.S. Civil War (1861-65), the Cambodian refugee crisis (1979-80), and the civil wars in Lebanon (1982-84) and El Salvador (1983-87).1 Simultaneously, more than 50 students enrolled in courses in English and Humanistic Studies were also engaged in the project through required course assignments. For example, in Digital Humanities Project Lab, students created a digital edition of ten personal accounts written by Cambodian refugees. In Introduction to the Digital and Public Humanities, students analyzed and assigned metadata to letters or photographs related to the wars in Lebanon and El Salvador. Students enrolled in Modern Literature created websites linking course readings with archival material related to the sisters’ nursing efforts (what became the model for the Naval Nurse Corps). By building a two-pronged approach—part grant-funded independent research project, part curricular ecosystem—we valued sustainability from the outset, which was an especially crucial factor given what was to come in 2020.

Initially, we partnered with two community organizations to bring these stories directly to the community through a public museum exhibit and guided conversation on viable responses to the crisis of displacement today. In the face of COVID-19, though, we were forced to pivot, foregoing in-person events, exhibits, and discussion in favor of more digital approaches. This shift also extended our timeline. While we initially designed the project to take place over one calendar year, our efforts and engagements ultimately concluded more than two years after we began, culminating in November 2021 with a semi-public (due to COVID restrictions) exhibit, presentation, and workshop for the Saint Mary’s community and the Sisters of the Holy Cross. Letters, photographs, artworks, newspaper clippings, and handwritten personal narratives from Cambodian refugees were among the artifacts that remained on display in the College library for several months. In an effort to generate conversation, our project showcase focused on hands-on archival inquiry rather than a formal presentation. Student researchers facilitated small group discussions of primary documents and encouraged participants to consider issues of archival responsibility, or what Randall Jimerson calls “archival power,” as well as the material, textual, and historical conditions of production, preservation, and meaning-making.

Notably and unexpectedly, the author of one of the documents, a recently-retired sister, was in attendance, and she was able to reflect on her handwritten letter from nearly forty years previous, one which highlighted the conditions facing desplazados in San Salvador in 1983. Another sister noted, “We have lived and worked together for years, and I never knew that they did this work.” Comments like these function as reminders of the many forces at play—intentional and unintentional—in “hiding” important stories, from systems of selection and preservation, to the humbleness of the sisters themselves. There is risk, too, in misinformation. As attendees of a Catholic college founded by Catholic sisters, students often bring expectations—indeed, unproductive stereotypes—about women religious as docile, passive, or proselytizing individuals. As our archival work demonstrated with abundant clarity, however, these women were and are agents of change and advocates of justice. A student researcher remarked that her work in the archive “changed how [she] thought about relief efforts—the sisters really focused on need without creed.” Another student reflected on how much she learned about El Salvador and the sisters, since these “were [topics] not typically covered in class.”

Happily, these topics—and more—will continue to find audiences on campus as part of a newly formed Digital and Public Humanities minor, which was directly inspired by the success of The Displacement Project. With the support of a NEH Humanities Connections Grant (awarded in 2022), faculty in several humanities disciplines have partnered with colleagues in Computer Science and Business to ensure that our students have ongoing curricular opportunities to recognize, voice, and act on behalf of the important role the humanities play in public life.

Laura Williamson is an associate professor of Humanistic Studies at Saint Mary’s College (Notre Dame, IN). She is a scholar of early modern English literature and culture, the coordinator of a public humanities lecture series, and a founding faculty member of the Digital and Public Humanities minor at Saint Mary’s.