The Maus Project: Exploring Censorship and the Power of Literature

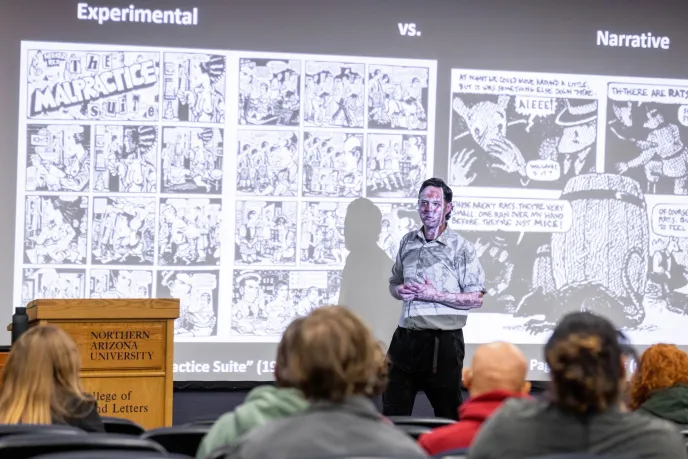

Dr. Robert Wallace, Maus Project contributor. Image courtesy of Steven Toya.

When a Tennessee school board unanimously voted to remove Art Spiegelman’s graphic memoir Maus from its 8th-grade curriculum on January 10, 2022, my colleagues and I quickly organized a virtual teach-in, “Baffled by Book Banning? Censorship and the Case of Maus.” We were four academics: a literary scholar, a political scientist, a philosopher, and a religious studies scholar. We needed to come together for some collective meaning making, and judging by the puzzled reactions of our friends and students, our community might also benefit from the space to ask how and why. How could a beloved graphic memoir, the winner of a special 1992 Pulitzer Prize, be banned? Why did this school board, and increasingly others, find it necessary to remove a long-time staple of Holocaust education from its library shelves? Maus is told as an animal allegory and takes up significant issues related to the Holocaust: genocide, war, trauma, memory and storytelling, family relationships, political power, and personal survival. We assumed access to this important text would always be with us.

On the night of our teach-in, nearly two hundred campus and community members crowded our Zoom screens, waving copies of Maus into their cameras, sharing favorite panels, asking questions, and voicing the fear, “what’s next?” After the event, our team was convinced that it was time to deploy the tools of the public humanities—collective meaning making, democratic engagement, interrogation of power dynamics, and the creation of empathy—to understand why Maus was banned and censorship was on the rise in the United States. In 1981, a year before the first American Library Association-sponsored Banned Books Week, a record 200 books were banned, threatened or challenged, a rise ALA found disturbing. In 2021, 1,597 were banned, threatened, or challenged.

Our small group of teach-in leaders pondered how to proceed. Believing, as Edward Said did, that there is “no contradiction at all between the practice of humanism and the practice of participatory citizenship,”1 we decided to launch a weekly, interdisciplinary, public humanities seminar for students that would also be open on a walk-in basis to members of the community. The Maus Project would meet each Tuesday for twelve weeks, drawing eager students, public school teachers, faith leaders, small business owners, city council members, and curious retirees for guided discussions on some aspect of Maus. Some would be reading Maus for the first time; some, like myself, would bring their dog-eared, duct-taped, oft-read copies each week to the seminar room.

In a university setting, it’s often difficult to quantify or value team-teaching, but I found no shortage of colleagues who eagerly agreed to donate their time and take on a seminar session. The only criteria, I told my fellow professors, was to ground their discussion in the graphic memoir itself and challenge audience members to turn to its pages for example and inspiration. A philosopher led us in a discussion about the cultivation of the moral imagination; a professor of women’s and gender studies described identity and women’s voices; a political scientist helped us understand the history of displaced persons; a director of a center on the teaching of tolerance showed us how trauma is intergenerational; a literary scholar examined the genre of memoir; a political theorist charted the rise of antisemitism and other hate crimes; an art historian addressed the way museums remember the Holocaust; librarians led a Banned Books Week scavenger hunt in community libraries and bookstores; and a teacher educator created space for discussions of literature and social justice education, culminating in a lively mask-making project that encouraged the audience to imagine how we negotiate our differences in group settings. Each week members of the audience found a panel or page of Maus they felt compelled to share, using the overhead projector’s light to illuminate discussions about fathers and sons, racism and oppression, the banality of evil, and resilience and survival. Each week someone was moved to ask, What if this book weren’t available to us? What do we lose when ideas are censored, when history is sanitized, when opportunities for ethical engagement and civil discourse are threatened?

Having the dedicated space to ask how and why each week resulted in new discoveries about the text, about ourselves, and about the power of aesthetic representation. Together we encountered the ways literature is both an object of knowledge and a source of knowledge.

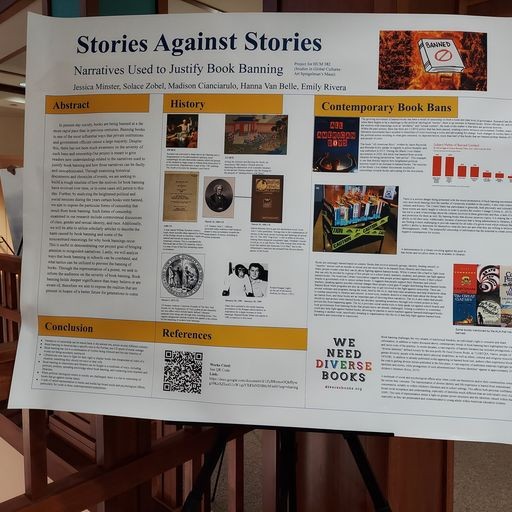

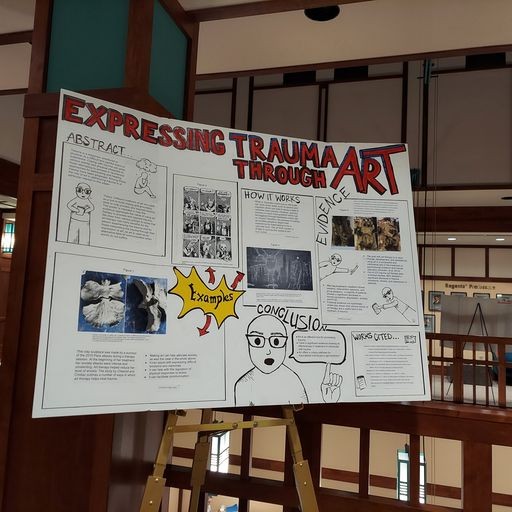

At the end of the semester, enrolled students presented their collaborative research to articulate why Maus matters. We held a celebratory yet somber poster event in our campus library, a fitting space in which to explore the imaginative power of literature and the chilling effects of censorship.

The Maus Project was not the first or last of its kind at NAU. In fall of 2021, inspired by Albert Camus’ 1947 novel The Plague, we ran The Plague Project with similar effects. Planning has already begun for The Climate Project in 2023.

As a literature scholar and public humanist, I am forever exploring how literature offers communities the opportunity to confront the challenges that vex us. Reading cultivates in us an empathy we might not otherwise develop. Reading with others “resonate[s] with special force when individuals come together to form a collective audience.”2 Reading Maus together helped us acknowledge a unique, ground-breaking graphic memoir, and it directed our attention to the dangerous rise in book banning across the country. Public humanities engagement helped us strengthen our local democracy, too: we are now better prepared to confront and articulate the critical importance of the freedom to read.

Gioia Woods is professor of Humanities and chair of the department of Comparative Cultural Studies at Northern Arizona University.