In Crooked Tree, Belize, Eleanor Harrison-Buck of the University of New Hampshire and Sara Clarke-Vivier of Washington College are working with community members to build an archaeology museum and cultural heritage center dedicated to Belize’s Kriol (Creole) culture. Kriol descend from enslaved African and European populations that came together through early logging along the Belize River. While over a third of Belize’s population identifies as Kriol, K-12 students tend to be taught primarily about Maya archaeology and colonial history. The museum, which opened in the summer of 2018, will help fill this gap in partnership with the Kriol community of Crooked Tree, creating resources for teachers to integrate Kriol oral histories, material culture, images, and stories into the national curriculum.

Harrison-Buck first came to Belize as an archaeologist studying the ancient Maya culture. Harrison-Buck has directed the Belize River East Archaeology project since 2009, exploring the archeology of the lower Belize River watershed from the Preclassic to Colonial periods. Over the course of this project, Harrison-Buck and her team became increasingly focused on the country’s more recent past.

Kriol culture developed in the Belize River basin, as slave and logwood camps became villages in the mid-to-late 18th century. While many of these villages still exist, community life is changing more rapidly today than ever before. As highways have replaced the river as the primary means of transportation in Crooked Tree and across Belize, nearly all Kriol villages have experienced depopulation through migration to communities closer to the highways.

Amid these changes, Harrison-Buck and her colleagues have been working with community leaders to create museum exhibitions and educational materials in an effort to document and promote Kriol history and cultural heritage.

The museum building in Crooked Tree was donated by the village. It is a locally engaged project on every level.

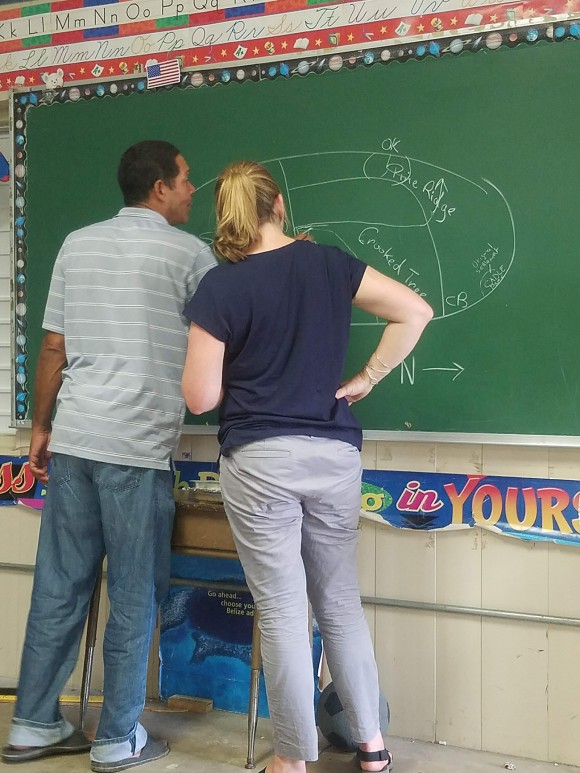

“The exhibits themselves are being developed in collaboration with community partners including the teachers in schools, with the goal of creating content that augments their existing social studies national curriculum,” Harrison-Buck explains. “In a lot of ways, it's co-authorship. I'm listening. I'm not just doing a project that’s for them to tell their history, but in fact they are helping to tell their history.”

For example, Harrison-Buck commissioned and documented the production of a paddle and dugout canoe, carved from a single trunk of a tree by a local craftsman which is on display in the museum. Visitors not only learn about this traditional practice, but are also encouraged to sit inside the dugout and picture themselves paddling all the way to Belize City, an arduous journey that took three days downriver and even longer upstream on the way back. Harrison-Buck noted, “When we talked with teachers and community members, one thing we heard over and over again was that young people don’t know what life was like in the past and are disconnected from their history.” In their discussions with the teachers in Crooked Tree, one of them commented about his students: “When they see things it takes the mind way back.” Along these lines, the museum emphasizes material culture and hands-on opportunities as a means of getting school children engaged and excited about their history.

Sharing oral history, local informants tell Harrison-Buck’s archaeological team where to dig and they help make sense of what is uncovered.

“Simple stories make a space and a landscape all of a sudden come alive,” Harrison-Buck reflects. “It informs where we excavate and it informs how we interpret what we're finding because they're part of the story. In that regard, they're not just recipients but active informants and involved in that reconstruction.”

For example, oral history helped the Belize River East Archaeology team understand what they found at the site of the village’s old schoolhouse.

“We were able to say more about where we were working because of what our local partners could tell us,” Harrison-Buck explains. “The school was operating until the 1940s, so there were a few elders who could describe to me what it was like going into the school… the kinds of inkwells they would use, the slates they would write on. When [students] got older they were allowed to use ink with paper, but when they were little and on the first floor of the school they had to use slates. Sure enough, when we excavated we found tons of slate writing implements.”

Over the course of the project, Harrison-Buck found that objects started conversations.

“You take an object which seems static and kind of dead and all of a sudden people start talking about it, they talk around it and you hear all these little stories and vignettes,” Harrison-Buck explains. With items like a slate board in the museum, the project hopes that they will continue to have this energizing effect for years to come.

Learn more about the Crooked Tree Museum and Cultural Center on their website and Facebook.