Using the poetry of Baltimore’s young people from the 1960s-80s published in Chicory Magazine, the Chicory Revitalization Project is engaging high school and college students in conversations about the city of Baltimore and its history. With funding from the Whiting Foundation, Rutgers University history professor Mary Rizzo has leveraged collaborations with trusted community organizations to bring Chicory Magazine back into the public domain in creative and accessible ways.

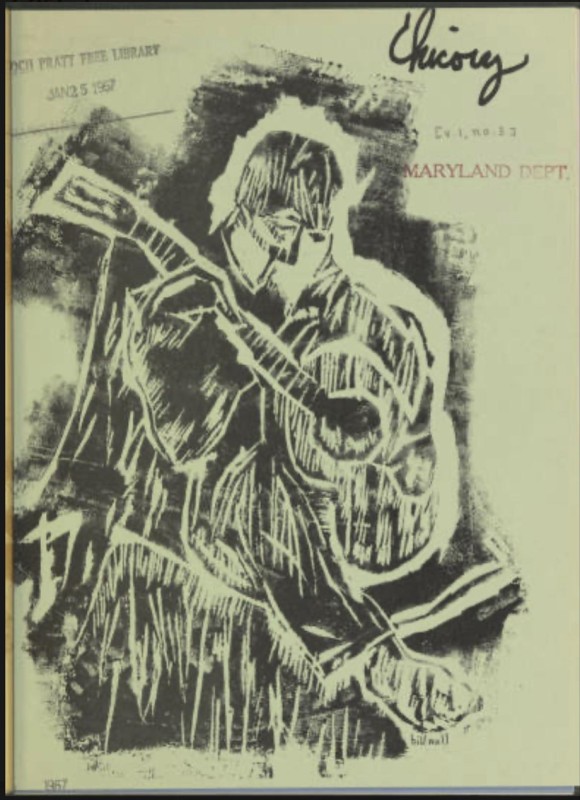

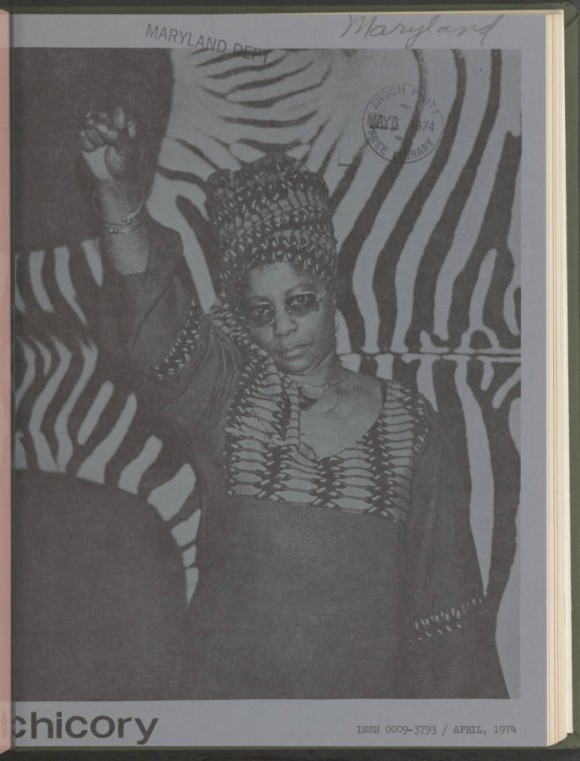

Chicory was a publication in circulation from 1966-1983 that printed poems, stories, plays, and essays by working-class Black Americans living in Baltimore. Yet more than a literary magazine, Chicory was itself a public humanities project. Funded with War on Poverty funds and housed within the Enoch Pratt Free Library, the magazine’s editors (Sam Cornish, Lucian Dixon, Augustus Brathwaite, Melvin Brown, and Everett Adam Jackson) partnered with organizations and institutions around Baltimore—such as a school for pregnant teens and the local jail—to find willing writers. Not only did Chicory encourage community members to engage with Baltimore’s cultural institutions, Chicory was also a voice of the Black Arts Movement, offering, in the words of Cornish, “people who don’t like to write but have something to say” a space to convene around a shared Black identity and social justice issues.

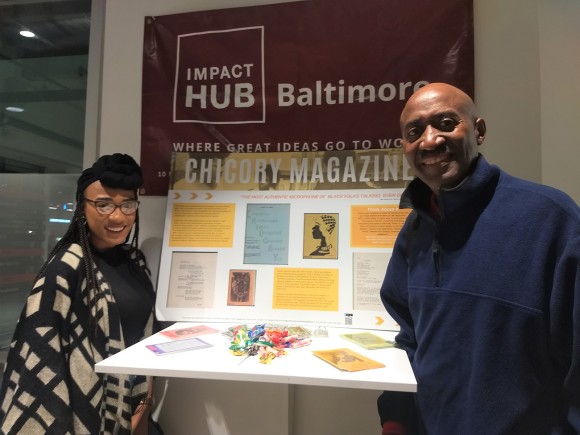

Consistent with Chicory’s earlier role, the Chicory Revitalization Project has digitized the magazine’s full corpus and is using the magazine as a primary source to guide writing workshops, surface local oral histories, and inform classroom projects that draw out the relationship between Baltimore’s past and its present. Rizzo first encountered Chicory in Pratt’s archive while doing research for her book Come and Be Shocked, which examines how Baltimore's urban leaders from the mid 20th to early 21st centuries have used art to shape how the city is seen and how artists have fought back through their own representations. In working to make Chicory accessible to the public again, Rizzo—herself a university researcher located in Newark— knew that for both logistical and ethical reasons horizontal partnerships with well-respected community organizations would help the project connect with the city’s youth in impactful and enduring ways. In 2018, Rizzo used her Whiting Foundation Seed Grant funding to assemble the Chicory Advisory Group, a team made up of Baltimore community members and stakeholders invested in Chicory’s future, including two of the magazine’s former editors, Melvin Brown and Everett Adam Jackson.

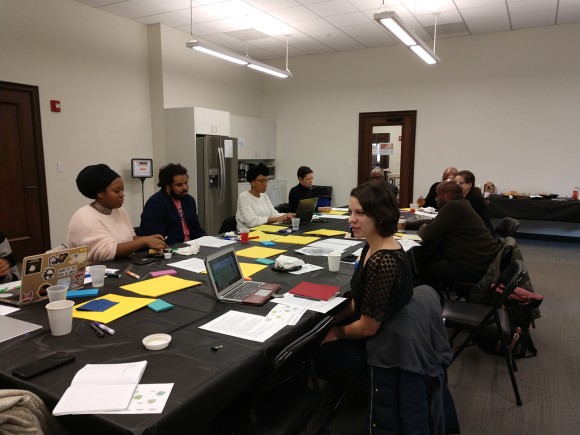

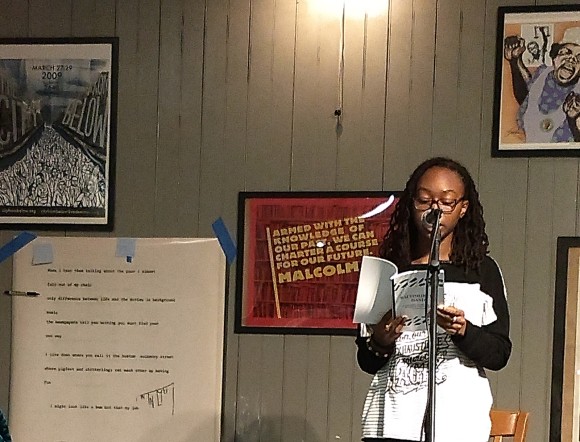

As a result of those initial Advisory Group conversations, Chicory’s wide-ranging content is being used as a foundation for community writing workshops and student events across Baltimore. During an event in celebration of the one year birthday of DewMore Baltimore, a cultural organization that uses poetry and art to foster civic engagement with Baltimore’s historically marginalized youth, students celebrated the city by drawing connections between Chicory’s content and their own lives. Students read and discussed selected poems, created their own art in response, and shared their works during an open mic session. Other events with Writers in Baltimore Schools, an organization that hosts after school writing programs with middle school and high school students, have similarly used Chicory during their Senior Reading and Year-End Showcase. These events treat Chicory’s poetry as an entry point for students to better understand the past and make connections to the present.

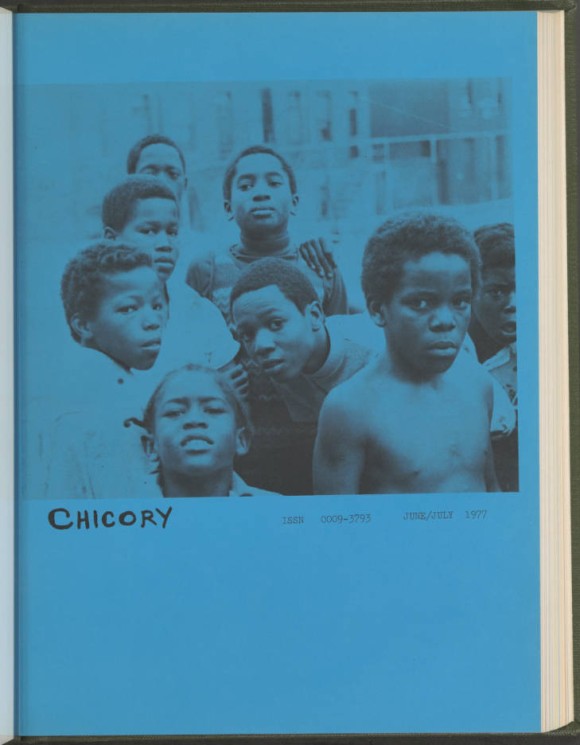

Rizzo noted how in these workshops students are particularly keen to draw out similarities between the social issues of Baltimore’s past and their endurance in the present, particularly the prevalence of anti-Black violence and over-policing in the Black Lives Matter moment. Rizzo reflected: “Certainly the students are living in the aftermath of the murder of Freddie Gray and the ‘riots’ or uprisings that happened in Baltimore in 2015. Because Chicory encompasses the late 1960’s era of urban unrest there is a real kind of connection point there as they are trying to figure out what it means to call something a riot or uprising.” Conversations in student workshops not only prime important civic dialogue around issues specific to Baltimore but also make space for conversations about identity. As Rizzo noted, “these are young people, they're figuring out their own identities. So, not everything that they're interested in is about The Social in terms of big historical ideas. A lot of what they’re interested in is about themselves and relating to people who were like them.”

In her own undergraduate teaching at Rutgers, Rizzo has also used Chicory as an example of place-based public history for her students and developed a final project in partnership with the Peale Center for Baltimore History and Architecture. In her intro to urban history class, Rizzo asked her students to read and respond to poems from Chicory that were connected to a specific place in Baltimore and that spoke to them personally. Students then produced audio essays that contributed to the “Be Here Stories” collection housed on the Peale Center website. In other courses, Rizzo has used Chicory poems alongside historical documents as a way of drawing out differences in narrative and perspective for students.

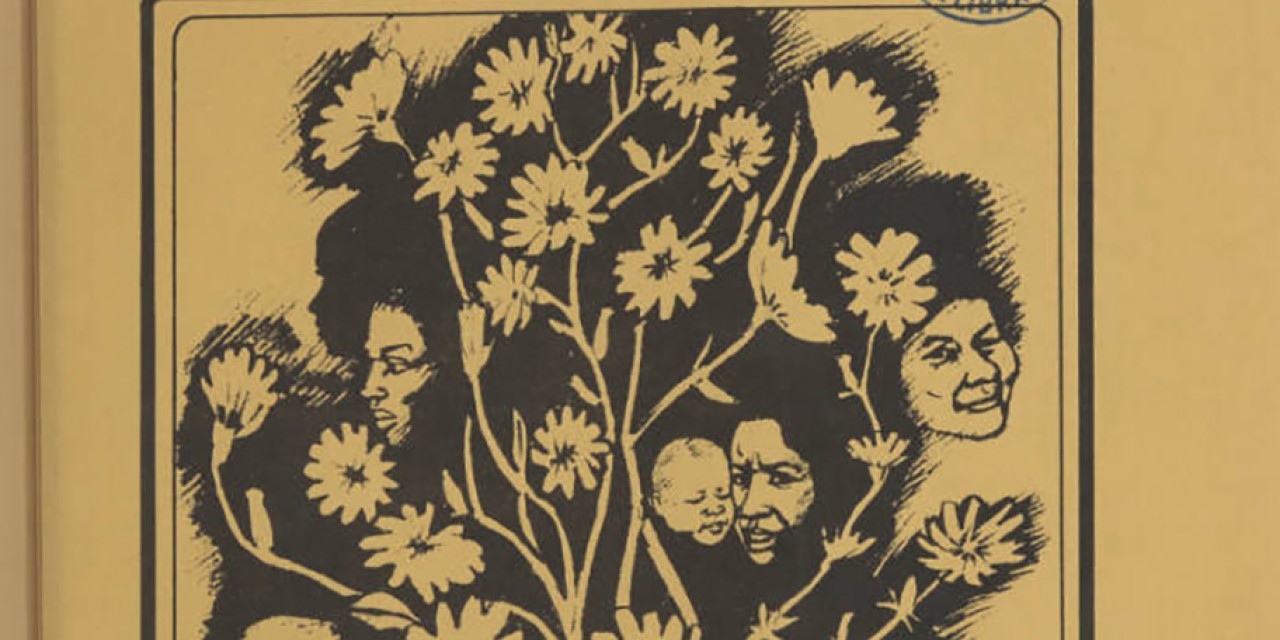

Beyond the classroom and workshop spaces, Rizzo has used the work of digitizing Chicory to ensure that the magazine is not only preserved for future generations but also broadly accessible, which she sees as a question of equity. Rizzo, who is also the associate director of Public and Digital Humanities Initiatives at Rutgers, saw the need to “break open the digital archive” for young people and extend the public reach of Chicory beyond its virtual repository on Enoch Pratt’s Digital Maryland website. The Chicory Revitalization Project’s Instagram page, created by Rutgers American studies doctoral candidate Sydney Johnson and run by American studies masters student Crystal Robinson, has served as one way of bringing Chicory’s rich visual content to the public. The page invites viewers to read the history of Black cultural production and expression onto Chicory’s cover art and content, offering opportunities for conversation among followers in the comments through reflective writing prompts and questions.

As the project grows Rizzo hopes to continue this digital preservation and access work by creating a website for Chicory’s poetry to exist as both art and historical document, where interviews with former editors, critical essays, virtual exhibits, and reflections enrich readers’ ties to the magazine.

February, 2021