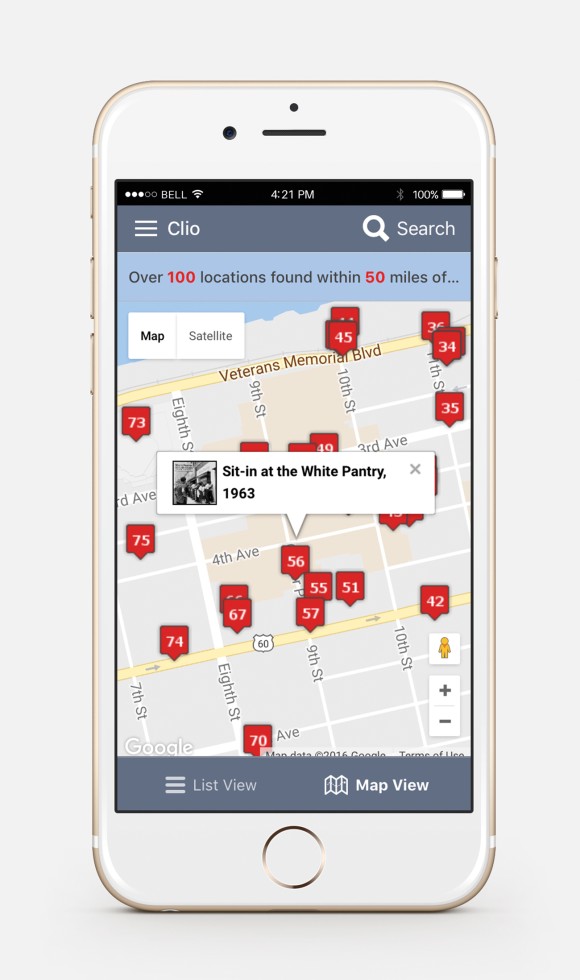

Clio is a free mobile app and website that uses GPS to share local knowledge about historic and cultural sites around the United States. Created by David Trowbridge of Marshall University, Clio is driven by a nationwide network of contributors from communities and institutions—including classes at universities and colleges—who know their history and want to share it with the world.

As of January 2018, Clio has nearly 30,000 entries and over 200 walking tours from across the country including historical and cultural landmarks, monuments, and museums.

Clio is above all accessible, with an intuitive and user-friendly interface.

“The first thing you’ll notice when you open up Clio are the 20 sites nearest you,” Trowbridge explains. Each entry contains a short introduction to the site and its history, with images, media, and links to further information including scholarly articles and books.

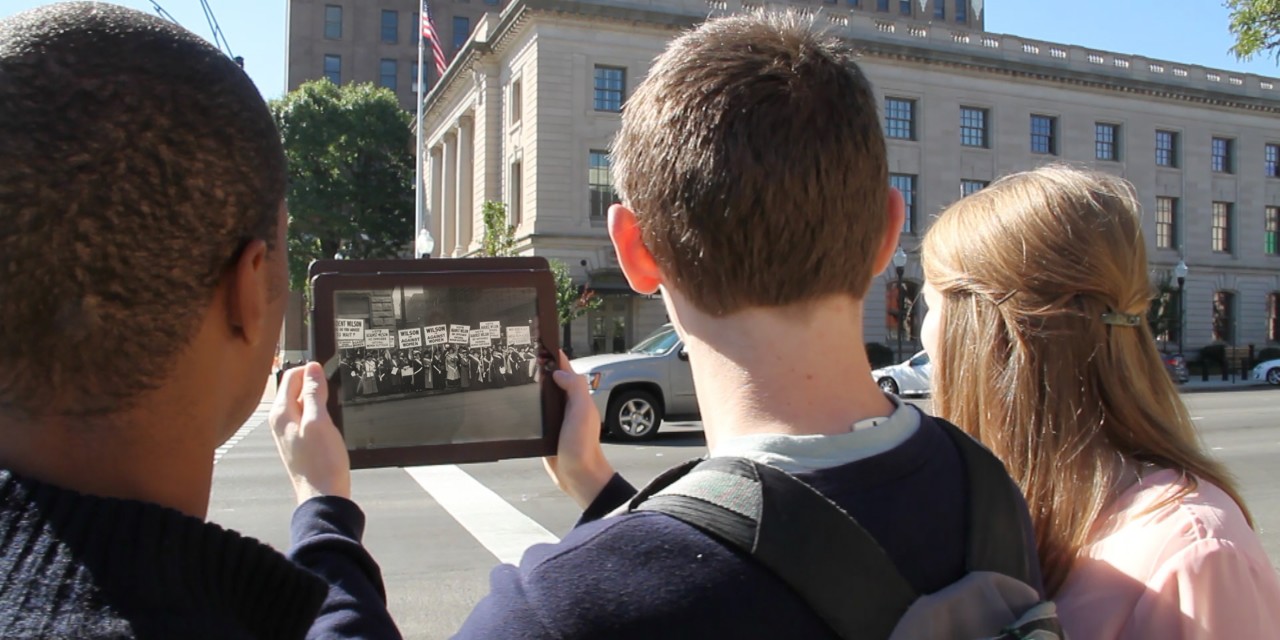

“People and organizations all over the country are creating new entries and improving them each and every day,” Trowbridge explains. With these entries, the project brings the museum experience to the outside world.

“I try to think like a museum,” Trowbridge says. “Museums are fun, and you can experience them at your own pace. Each entry gives the ‘museum label’ introduction; history is more than names, dates, and places, but you have to establish that first. If you want to read on, the second section gives the rest of the story. Once we’ve ‘hooked’ them, we say, here is an article or book on the topic or a primary source. We try to meet curiosity with expertise.”

Clio is able to share such a diverse collection of resources because it draws on local expertise around the country, including community members and contributors in higher education classes and at museums, libraries, and historical societies.

When presented with such a range of options, Clio finds that people are naturally curious.

“What we've found is people click on everything,” Trowbridge says. “My specialty is African American history. I know when people download Clio, they aren’t downloading a Black history app—but they… click on black history sites. They click on the books and they click on the articles and they click on everything.”

Anyone can contribute to Clio, creating and updating entries. When community members contribute, their entries are reviewed by administrators. Clio gives institutional accounts to libraries, historical societies, and museums, enabling them to directly develop entries.

“For most people, Clio is a website and an app,” Trowbridge explains. “It’s a product. And it is—but the process is probably more valuable than the final product.”

Clio enables collaboration between people who have never met.

“If you were creating an entry for the ballpark where the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro League used to play, the scholar has information and can craft a concise narrative,” Trowbridge says. “But the librarian or the archivist has an oral history of Buck O’Neil that they can add to Clio; and the local people can add their memories and what it meant to them to watch the Kansas City Monarchs beat the Kansas City Blues. All of that is happening on this platform between people who don’t know each other.”

Clio in the Classroom

Clio is specially calibrated for use in education, with built in systems to make incorporating Clio for assignments easy for instructors and students.

Educators are given special accounts, enabling their students to easily plug in. To begin, students need only to find their professors on a drop down menu and enter a shared password—then they are ready to review Clio’s instructional videos and get to work creating entries and walking tours. Their professors can then review drafts of their students’ entries.

“Professors can easily create entries with their students, evaluate them, provide feedback, and publish them,” Trowbridge explains. “Each entry has the name of the organization and the author—the name of the professor, the university, and the student, so that there is mutual accountability.”

As easy as the interface is, the work is challenging and Trowbridge recommends ongoing student support and curricular scaffolding throughout the semester.

“You’re asking your students to do publishable work and that requires one-on-one time with students. I meet with students three times throughout the semester to talk about their work,” Trowbridge says. “But if you do that, if you show them what a good entry is, if you tell them why they’re doing the work, if you talk about the skills they’re developing, if you give them the freedom to explore topics that interest them, and if you encourage them to match up with a librarian or a writing center, it really is a joy.”

Professor Ed Ayers, of the University of Richmond, has used Clio in his classroom. “When sixteen first-year students in my seminar interpreted the University of Richmond’s landscape last year they saw not only their campus but history itself in a new way,” Ayers noted to Marshall Magazine, “Thanks to Clio, their work benefits everyone who lives, works, studies, and visits here.”

Clio is Not for Profit

Clio is now run out of the non-profit Clio Foundation. Working out of a higher ed institution and an independent non-profit enabled Trowbridge and the Clio team to not be concerned with keeping users in the app or on the website.

“Clio is designed to drive traffic away from Clio, to books, articles, digitized primary sources, oral histories,” Trowbridge explains. “I want people to buy books, to leave Clio and to go to a library site and go to a library and to realize how important libraries and archives are. It’s a mobile app designed to get people off their phones…. It’s respecting what people are interested in, their curiosity—and offering authentic good information connecting curiosity to expertise and letting them explore.”

The Clio Foundation also helps ensure the sustainability of Clio as a platform for engaging with the past. “When we talk about sustainability in digital projects we often speak only of technological and financial matters,” Trowbridge explains, “Creating a non-profit foundation was not simply a way to handle donations and offer sustainability should something happen to me, but also about finding a core group of people who would sustain the mission.”