At Columbus State University, the Columbus Community Geography Center is advancing student learning and sparking local economic revitalization. Coordinated by Amanda Rees, the Center’s classes are built around student research projects run by, with, and for diverse community partners. Community geography uses the tools of geography, like GIS and mapping, while drawing knowledge and direction from the community, Rees explains. “We bring the [field’s] ways of doing things, but they bring content or we’re discovering content that they know is out there, they just don’t know how to get to it.”

The Center’s projects have included the creation of lesson plans on spatial reasoning and urban planning with Girls, Inc., a nonprofit organization focusing on the empowerment of young females; a report on food pantries and food accessibility with Feeding the Valley, a Columbus, Georgia-based food bank; and a community-sourced map and place-making project focusing on Buena Vista and Marion County, Georgia with the Buena Vista Chamber of Commerce.

Reese explains that collaborations with local partners have sustained the interest of the university’s diverse student population. “If students can't see an application for what they're doing, it can be a little dry and not very engaging,” Rees says. “Together, we've found that mixing community engagement and reflection can really be important to help students be energized and connected and feel useful.”

Building and strengthening these partnerships requires ongoing engagement throughout the course. “Managing that buy-in is quite important,” Rees explains. “Very early on in our pedagogical process, our community partners need to connect with the students directly. They come in to give a talk to the students. I’m very clear in what I need, which is: What is your mission? What is the project? How is this going to help you do what you do in the future? What’s the meaning? Why are we bothering? We see them in the process. At the end of the courses, the goal is to meet again with the partner to present our findings.”

The project in Buena Vista and Marion County, Georgia is illustrative.

“There is a small county, probably about three-quarters of an hour away from Columbus. Small, rural, lost a chicken processing plant about 3 or 4 years ago which meant 200 jobs which was a massive impact to this small community,” Rees recalls. “At the same time, there is a ‘visionary art environment’ in this community.” The environment, called Pasaquan, was created by Eddie Owens Martin, who died in the 1980s. “The Pasaquan Preservation Society kept it going by hook and crook,” Rees states. When the Kohler Foundation came in to conserve it in 2014, the State of Georgia recommended that the Chamber of Commerce develop a heritage tour and trail to leverage the foundation’s investment.

Ress’ students stepped in to help by creating maps of the city and the county with local residents in collaboration with a graphic arts class at the university.

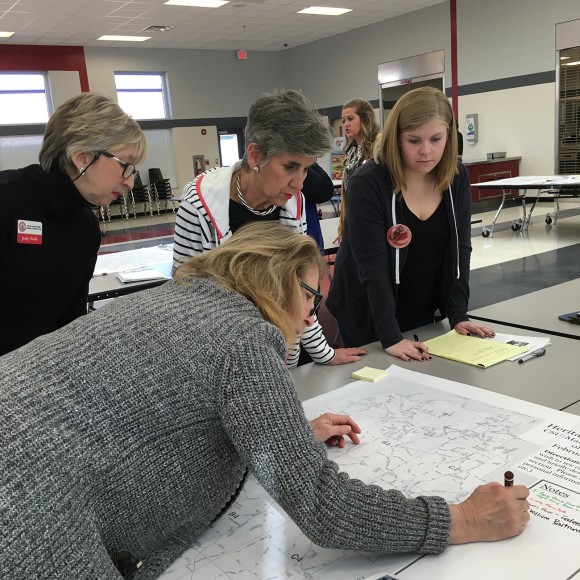

“We interviewed lots of people. We had a workshop one Thursday in the spring and invited people from the community to come,” Rees explains. “My students stood at stations with these large city maps and county maps and asked people to share places that they thought would be of interest and important to people from the outside…. A few places were more legend than fact. We had to treat that language a little differently, but it was important for folks to share that, and it gave a really particular sense of place.” With community input, the geography students made the final decisions on content and then the graphic design students got to work.

The maps were for visitors, but created by, with, and for the community. “Even though the audience is the visitor, we are are always mindful that we are helping a community tell its own story to itself,” Rees notes. “We're mindful of making sure we're representing difference and not reiterating histories that aren't inclusive. We bring our professional sensibility to our practice.” With this in mind, the community came together to launch the maps. One thousand five hundred maps were distributed that day, impacting the community’s sense of its own place and creating opportunities for tourism and economic development. The mapping and place-making efforts have paid off in garnering outside attention: in 2016, CNN named Pasaquan one of “16 Intriguing Things to See and Do in the U.S. in 2016.”