The DNA Discussion Project uses commercially available DNA ancestry tests to open up conversations about race and identity. Led by Anita Foeman and Bessie Lawton of West Chester University of Pennsylvania, participants have their DNA analyzed and then come together to discuss the questions their results sometimes raise: Were the results what participants expected? What do they mean for participants and their understanding of race, self, and community?

The project takes place largely on West Chester University’s campus, though Foeman and Lawton do bring the project to other universities and organizations.

The DNA Discussion Project grew out of Foeman’s experience facilitating diversity training programs and excitement about the human genome project.

“I saw that in the human genome project you could look at people’s ancestry,” Foeman recalls. “I remember thinking there are a bunch of people walking around with this narrative about race and putting people in ‘silos.’ I bet their profiles are much more complicated than that. As if by magic at the same moment this was coming together, our Multicultural Faculty Commission asked if anybody wanted to apply for these small grants and to do something that was nontraditional around race.”

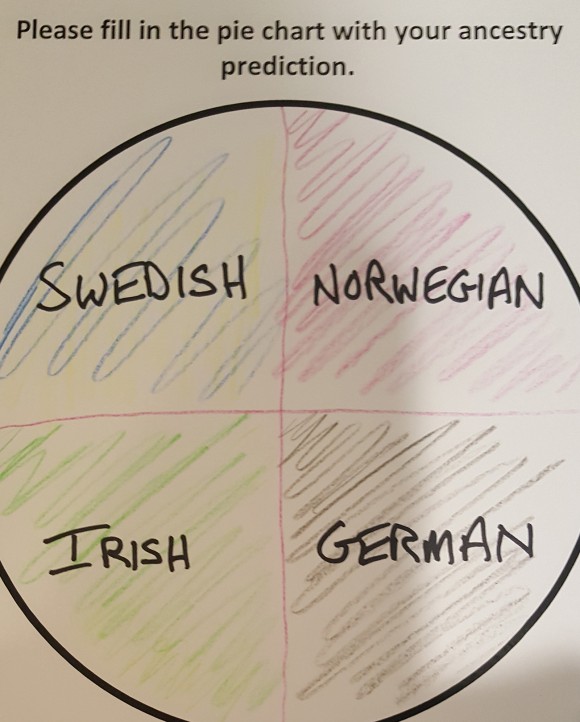

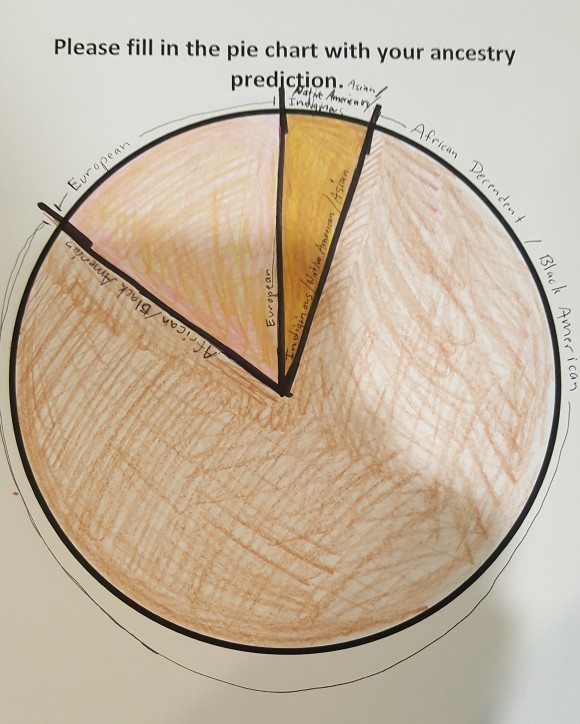

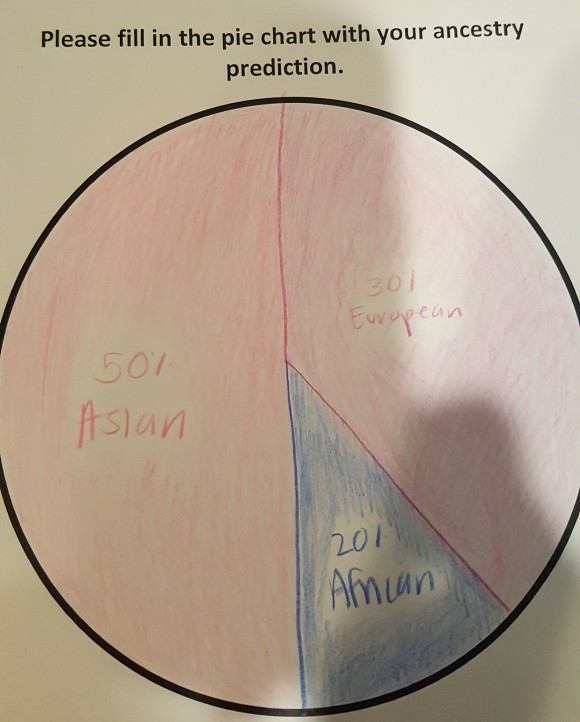

Foeman applied for and was awarded a $1,500 grant, which at the time covered three tests. “I tested one person who identified as black, one person who identified as white and one person who identify as biracial black-white. Now the readouts of the tests were not anything they are today. Today you get these really neat pie charts with percentages. At that time, it was a list of things that might be in your background. But even in that, you could already see that the story that we walk around with in terms of race was much too narrow,” Foeman recalls.

The project’s protocol has remained stable over the years, although it has been tweaked occasionally to shift research objectives for different grants. It begins with a pre-survey, in which facilitators ask participants what they expect and how they would define themselves racially.

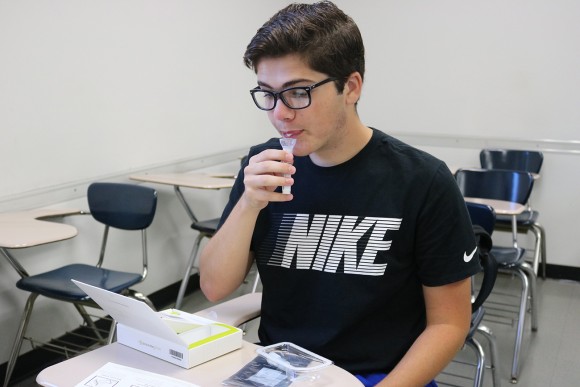

“Then we do the saliva test,” Foeman explains. “It takes about six weeks to get back. If I do it in a class, then we have reading and discussions [during that time]. But sometimes when we do it with community people with other mixed groups, people go away for a period of time and then they come back for the reveal.”

At the time when the results of the survey are shared, the group assembles to discuss the relationship between what they expected to find and what they found and to fill out a post-survey, which has led to a number of scholarly publications.

“There are really two kinds of conversations that take place,” Foeman states. “One is: What's the difference between what I expected and what I found. So it's internal and that's where we start. What surprised you about your own narrative? Can you explain it? What do you think? And then the second conversation is: How does this then join you to people in unexpected or expected ways?”

The conversation can be personal, of course. It can uncover things that can be uncomfortable. Discomfort is not necessarily bad, though. “If you can catch people off guard with their own story, then that's like rebooting the conversation around race,” Foeman says. “Because if I don't even know what my story is, then maybe I should be a little more humble about trying to identify what box somebody else fits into.”

Comparison of the pre- and post-surveys has enabled Foeman and Lawton to explore conceptions of race in a new way.

“We look at how [participants] responded, what they said on the pre-survey and what they said on the post-survey in terms of what surprised them,” Foeman explains. “We looked at the different attitudes that they have expressed about race or different groups. One project that we did was on interracial individuals and we wanted to look at how fluid people were in terms of their racial identity. We wanted to see if people who are already identified as multiracial were willing to change their racial identification based on a DNA test.” This and other studies are available on the project website.