Based out of Rutgers University-Newark, the Humanities Action Lab (HAL) is a global coalition of universities and community organizations that explores urgent, difficult, and often contested social issues through collaborative public humanities projects. HAL produces exhibitions and programming that foster dialogue and create new models for addressing issues through the humanities.

Local partnerships are key for the Humanities Action Lab, Assistant Director Margie Weinstein explains. “HAL partners create a major public project every three years that explores the history, memory, and current realities of a pressing social issue,” Weinstein says. “Each project includes an exhibit, digital platform, oral histories, face-to-face community dialogues, and interactive media. Students and community partners in each participating locality contribute their local histories and perspectives to the international project, which then travels to each community that created it, opening a space to generate and exchange unique locally-grounded approaches to common global questions.”

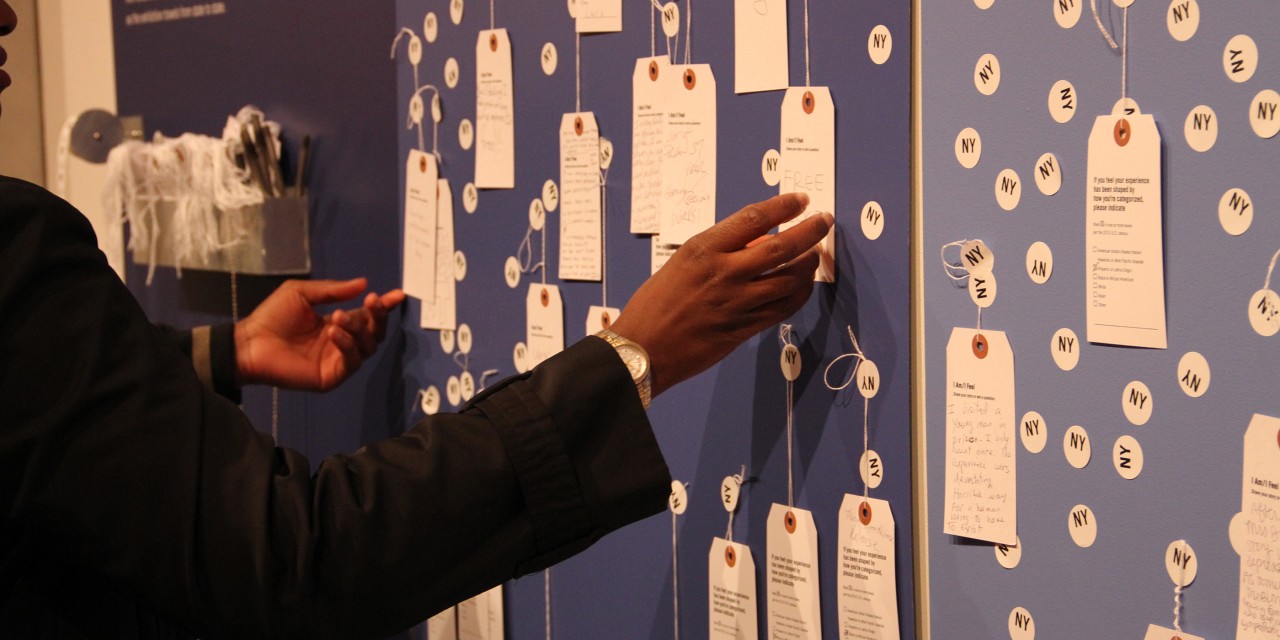

HAL is currently in the planning stages of a project on environmental justice. Previously, HAL partners developed local projects exploring mass incarceration called States of Incarceration. “[S]tudents worked with returning citizens and others impacted by incarceration in 20 cities around the country to create a traveling exhibit, web platform, and series of public dialogues on the roots of mass incarceration in each of their communities, and how to address it today,” Weinstein recalls.

In this work, Weinstein emphasizes the power of the humanities. “The humanities are critical to HAL’s activities, opening up deadlocked conversations by highlighting questions of history and memory. We do this by bringing historical perspective to contemporary concerns to examine how the past can inform the present and understand how we got here, by creating space for multiple perspectives that allow stories and memory to humanize issues that are often reduced to numbers and statistics, and connecting the local and inter/national by examining regional portraits of an issue that become assembled into an inter/national whole.”

HAL’s projects are student- and community-driven, a process that involves deep engagement and ongoing dialogue with a wide variety of stakeholders: community partners who have been impacted with the issues the project explores, faculty coordinators, and other HAL chapters across the U.S.

“HAL university [chapters] offer courses, through which students collaborate with community partners to curate a history of a local site of the issue as one piece of the international project,” Weinstein explains. “For instance, with States of Incarceration, DePaul University co-created their piece with students in an Inside-Out class at Stateville Penitentiary. Brown University students debated issues of crime and punishment for that chapter of the exhibit with men from the Rhode Island Adult Correctional Institute. The team at the University of California Riverside collaborated with directly impacted youth activists involved in the Youth Justice Coalition in exploring the school-to-prison pipeline.”

In States of Incarceration, each chapter contributed components grounded in local experience and research. They were then integrated into a national touring exhibition that visited the site of each chapter, grounding the project’s national view in work from around the nation. “[M]en and women directly impacted by the issue are involved at every stage,” Weinstein explains, “including a national working group that frames the traveling exhibition’s guiding questions and potential public interaction mechanisms allowing affected communities to create and share stories in an ongoing way as the exhibit grows and travels.”

HAL projects are guided by experts in history and public policy, who, Weinstein explains, are driven by “commitment, lived experience, and curiosity.”

“Student curators may have no background in the issue at all or have deep personal connections; they may have a strong intellectual foundation in one area but have much to learn in another,” Weinstein continues. “Community partners will always have strong direct experience and involvement in the issue; they may have no historical perspective on the issue or they may be experienced non-university historians and policy-makers. In any case, the process of selecting stories, images, and questions in each locality involves powerful discovery and difficult dialogue among people with a wide range of knowledge and experience, a significant experiment in project-based, action-oriented learning.”