“I’m Still Surviving” is an oral and public history and design project that documents, interprets, and presents women’s experiences in the history of HIV/AIDS in the United States. Led by historian Jennifer Brier at the University of Illinois at Chicago and designer Matthew Wizinsky at the University of Cincinnati as a part of the History Moves initiative, the “I’m Still Surviving” project is an innovative partnership with women living with HIV/AIDS in Brooklyn, NY, Chicago, IL and Raleigh-Durham, NC. Almost all of these women have been a part of the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS)—a longitudinal medical research project established in 1993. With “I’m Still Surviving,” the women become the researchers. Together with their university-based partners, they collect and analyze oral history interviews to produce books and travelling exhibitions on their experiences as women living with HIV. Through this collaborative work, “I’m Still Surviving” is broadening historical understanding of HIV/AIDS and breaking new ground in oral and public history practice.

Women—especially women of color—have often been excluded from the history of HIV/AIDS in the United States, Brier explains in an article in The Oral History Review. “HIV/AIDS is not, and has never been, an exclusively white gay male disease,” Brier notes. “While the first reported cases in 1981 were of white homosexual men, there were likely thousands of people—men and women, queer and straight, people living in poverty and those who were comfortably middle class—who were sick but not counted among the earliest cases.”

“I’m Still Surviving” represents an attempt to work with women living with HIV to tell their stories through collaborative oral and public history.

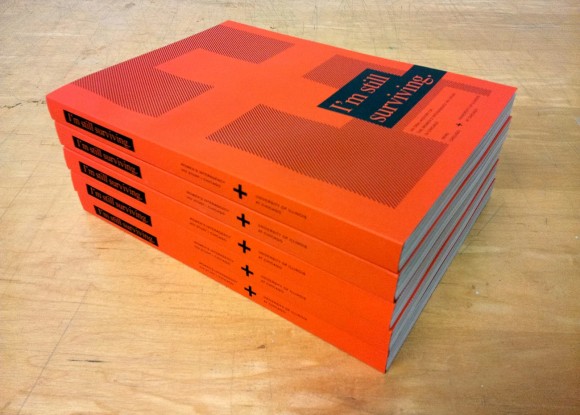

“In ‘I’m Still Surviving,’ women living with HIV/AIDS make and take space for themselves to tell their stories, and collectively and collaboratively interpret them through dialogue with one another. These stakeholders work together to intervene in the process of collection, curation, and interpretation of the history of HIV/AIDS,” Brier continues. “The public history component consists of three different public displays: a book featuring the oral histories and photographs from the fourteen [women living with HIV/AIDS], a short film with photographs and audio excerpts from the oral histories, and a pop-up exhibition, In Plain Sight, that displayed examples of all the materials (sound, image, text) and was installed at public libraries and art centers around Chicago in 2016.”

The foundation of this work was a workshop for the participants on how and why to conduct oral histories. After the workshop, participants got to work interviewing each other. “We paired the women so that they could interview one another. One of the History Moves team members attended each interview session, serving as technical assistant and second interviewer. Each interview unfolded differently,” Brier explains. “When women had known each other for decades, they were able to dig deeper into shared memories; when they met through the project, the interviews served as a place to build connections with other women living with HIV.”

Participants “held little back,” Brier notes.“More often than not, women who had spoken up about having HIV found support from the people they told.”

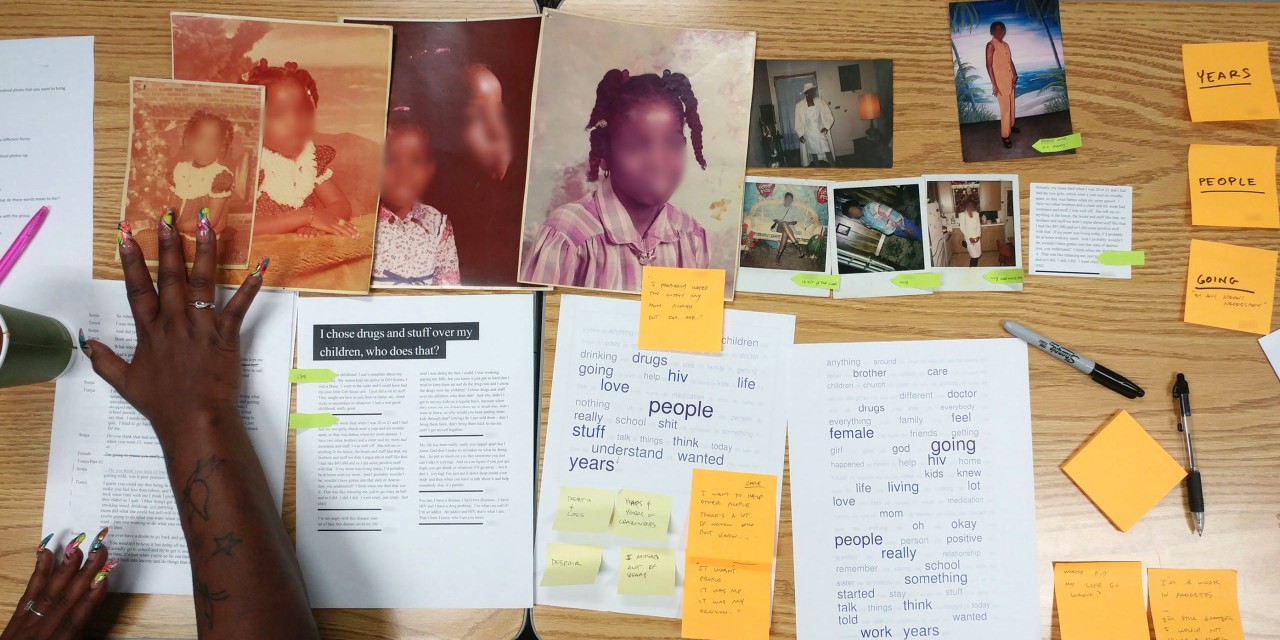

The women of “I’m Still Surviving” continued to be involved in the analysis of interview transcripts.

“We had the interviews professionally transcribed and returned printed versions to the women, not just with the intention that they would edit the transcripts, but also with the idea that they would begin to analyze them,” Brier continues. “Seeing their experiences on paper gave interpretive power to women who were not writers and who had not previously thought of themselves as narrators of written stories. The spoken words became text, while still retaining their unique voice.”

Participants vetted selections from the interviews and provided images for inclusion in the exhibition and media projects, collectively determining the narrative. “We all—historians, designers, and women narrators—sorted the selected texts and images into four thematic areas: early life, crisis, diagnosis, and still surviving,” Brier notes. The book and the exhibition were key outlets for the research, developed collaboratively by Wizinsky and the participants.

For example, the exhibition itself was designed by Wizinsky’s undergraduate students at the University of Cincinnati. The students worked together with the oral history materials and the women themselves, Brier explains: “It was really a challenge for them to think about the physical analog exhibition display, the narrative and the mechanisms that were included, and the social media component.” After the class produced their initial designs, Brier notes that the women of “I’m Still Surviving” helped shape the exhibition’s direction: “The [class] did a design review with the women in Chicago. We did a Webex and the women in Chicago looked at their initial designs and shared very pointed and excellent critiques of the work, which really helped them advance the work and think about [their] audience.”

The book and the exhibition are portable and have been used to bring the story of these women and HIV to their communities in Chicago. With funding from MAC AIDS Fund, the project is ongoing and has been expanded to Brooklyn, NY, and Raleigh, NC.