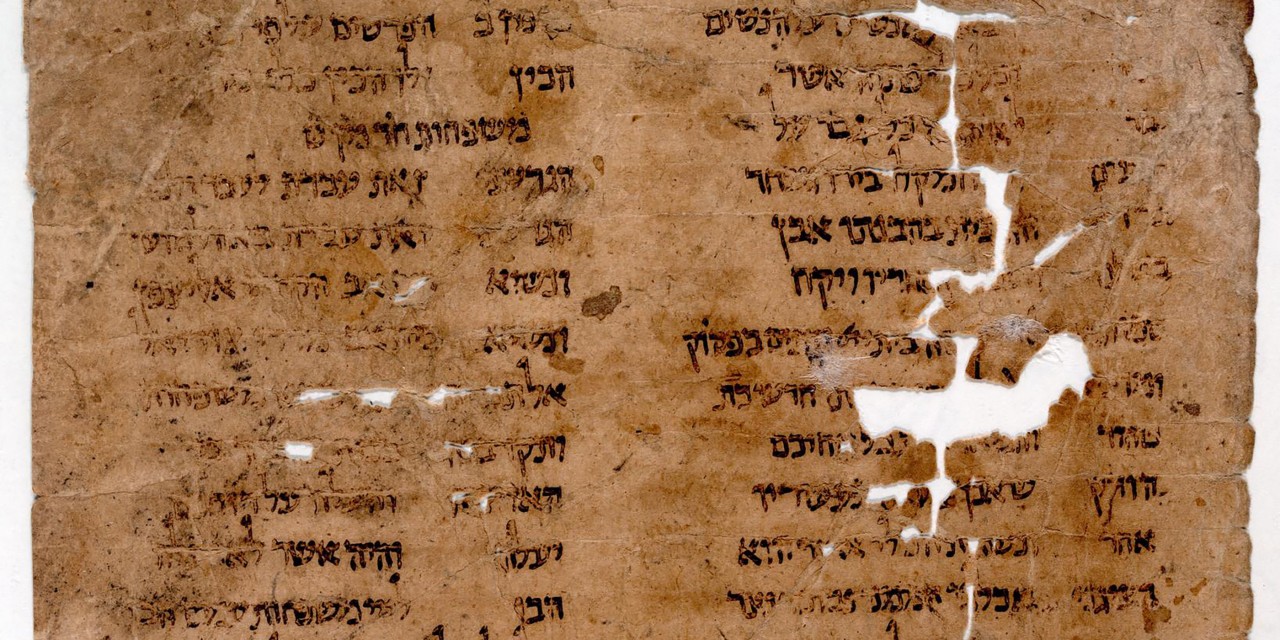

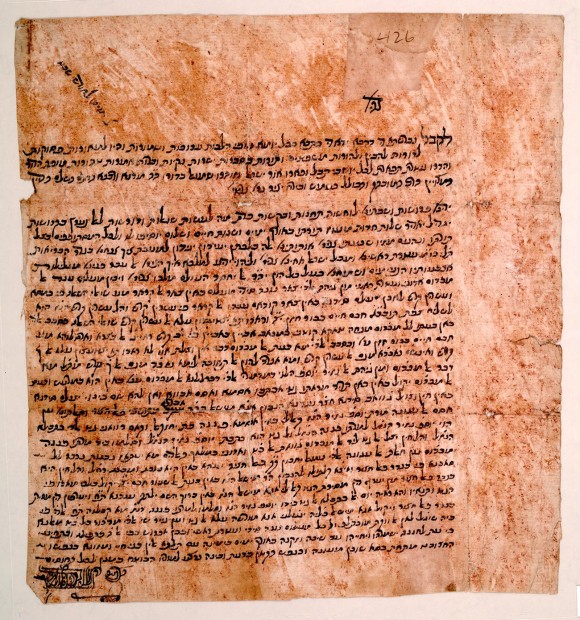

How do you transcribe 300,000 historic documents in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Arabic from the Cairo Geniza, a Synagogue storage area containing worn-out Jewish texts? According to a group of academic libraries and centers led by the University of Pennsylvania, you leverage the collective wisdom of crowds.

The Cairo Geniza’s diverse texts offer an unparalleled window into Jewish and non-Jewish cultural and commercial history in the region, especially during the 10-13th centuries. Though the Cairo Geniza has been studied since the 19th century, its documents are largely uncatalogued and are scattered in libraries around the world. In partnership with libraries that hold Geniza materials and the online crowdsourcing platform Zooniverse, Scribes of the Cairo Geniza mobilizes volunteer humanists to identify, decipher, and transcribe this physically dispersed but digitally reunited collection of Geniza texts.

Instructional video introducing Scribes of the Cairo Geniza. Video courtesy of Scribes of the Cairo Geniza.

With a sample size this large, dispersed, and diverse, Samantha Blickhan, IMLS Postdoctoral Fellow at the Adler Planetarium and Zooniverse humanities lead, suggests that crowdsourcing presents a fruitful way forward for research and public access.

“This data is used in... science, social science, or humanities investigations and should, ideally, lead to publication,” Blickhan says. Crowdsourcing also allows projects to connect with interested publics all over the world. “Online volunteering, enabled by crowdsourcing platforms such as Zooniverse.org, offer[s] an alternative or complementary form of engagement that has many benefits,” Blickhan continues. “Online projects can reach a wider range of individuals, including those who are less able-bodied or geographically remote from the institution in which they want to volunteer and/or unable to travel. This is particularly useful for a dataset like the Geniza fragments, due to their wide range of geographic locations across institutions. Similarly, online crowdsourcing allows these institutions to open up rare collections to the public without concern for their material safety and security.”

The first phase of the project recently concluded with 3,406 volunteers identifying languages and categories for 186,124 texts. To make these tasks feasible for those with no knowledge of the source languages, Scribes of the Geniza simply asked volunteers to identify characteristics of manuscripts by comparing them to reference samples.

“Scribes of the Cairo Geniza is a project with the ultimate goal of transcribing Cairo Geniza fragments,” Laura Newman Eckstein, Judaica digital humanities coordinator at the University of Pennsylvania, explains. “Before we could ask our volunteers to transcribe, we needed more information about the fragments themselves…. [W]e asked our community of volunteer humanists and historians to sort Cairo Geniza fragments into groups based on whether they were in Hebrew, Arabic, or both types of scripts. We also asked whether the scripts were written in an informal or formal style and about a few other visual characteristics that hinted at whether the fragment was religious or non-religious in genre.”

The second phase of the project will involve deciphering and transcribing the fragments. This phase has three goals, Newman Eckstein explains: to “provide our community of volunteer humanists and historians opportunities to view and decipher Cairo Geniza fragments; contribute to the classification of fragments by script-type and content; produce transcriptions of the material that will help in the work of historians, linguists, and other scholars of this material.” The transcribed material will be available in Penn’s open-access collection OPenn and as open data through other sources.

With this in mind, Arthur Kiron, Schottenstein-Jesselson curator of Judaica collections at the University of Pennsylvania Libraries, hopes that Scribes of the Cairo Geniza will serve both academics and the broader public. “My hope is that the Scribes of the Cairo Geniza project will not only serve the cause of research and discovery but will also provide unprecedented opportunities for people to learn to read seemingly illegible texts and to give everyone the opportunity to unlock and access this great chamber of handwritten medieval manuscript documents.”