In Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains, Gregory Samantha Rosenthal of Roanoke College is helping to lead a grassroots community-based public history initiative to tell the stories of Roanoke’s LGBTQ+ individuals and organizations. The Southwest Virginia LGBTQ+ History Project is organized through democratic monthly community meetings at the Roanoke Public Library. Rosenthal and the group’s other leaders have organized a range of initiatives, including the creation of a digital and physical archive, the collection of oral histories, monthly walking tours, and public programs including recreations of LGBTQ+ social events from Roanoke’s past. Through these initiatives, the project seeks to preserve history and facilitate conversation across generations in the LGBTQ+ community. Rosenthal explains, “We find that bringing people together to talk about history is a powerful way to break the ice and get those generations talking.”

The project is community-led, Rosenthal says. “The project is based at monthly meetings at the public library that are open to all. Since our very first meeting, we’ve invited people from the LGBTQ+ community to come out and they have set the agenda for what we work on,” Rosenthal notes. “We’re very focused on the ideal of democracy in doing this work and making sure that LGBTQ+ people are the leaders in this project and are taking the lead and are telling the stories about our community.”

Rosenthal’s students have been involved in the collection of oral histories in classes and as paid research assistants, but they join members of the local LGBTQ+ community in conducting these oral histories. Collectively, they have conducted 33 hour-long oral history interviews. “We've moved towards recruiting young members of the community to train to come in to do the interviews. We have LGBTQ+ people interviewing LGBTQ+ people, rather than mostly straight students. That was something we wanted to move towards,” Rosenthal notes, explaining that the identity of interviewers can impact interviews.

But there also is a broader reason for ensuring that community members take the lead. “Our project is about creating leaders and empowering leadership,” Rosenthal explains. “The goal here is to pass on skills. In fact, we have volunteers who are involved in accessioning archival collections, digitizing and putting in the metadata for digital collections, leading public walking tours, conducting oral history interviews. These are all things I learned to do in graduate school studying public history, but they're things we have trained young LGBTQ+ people in the community who are not affiliated with the university to do. It provides a sense of ownership over these stories. We feel that LGBTQ+ history is our community’s story and it’s on us as LGBTQ+ people to decide how we want to tell the story.”

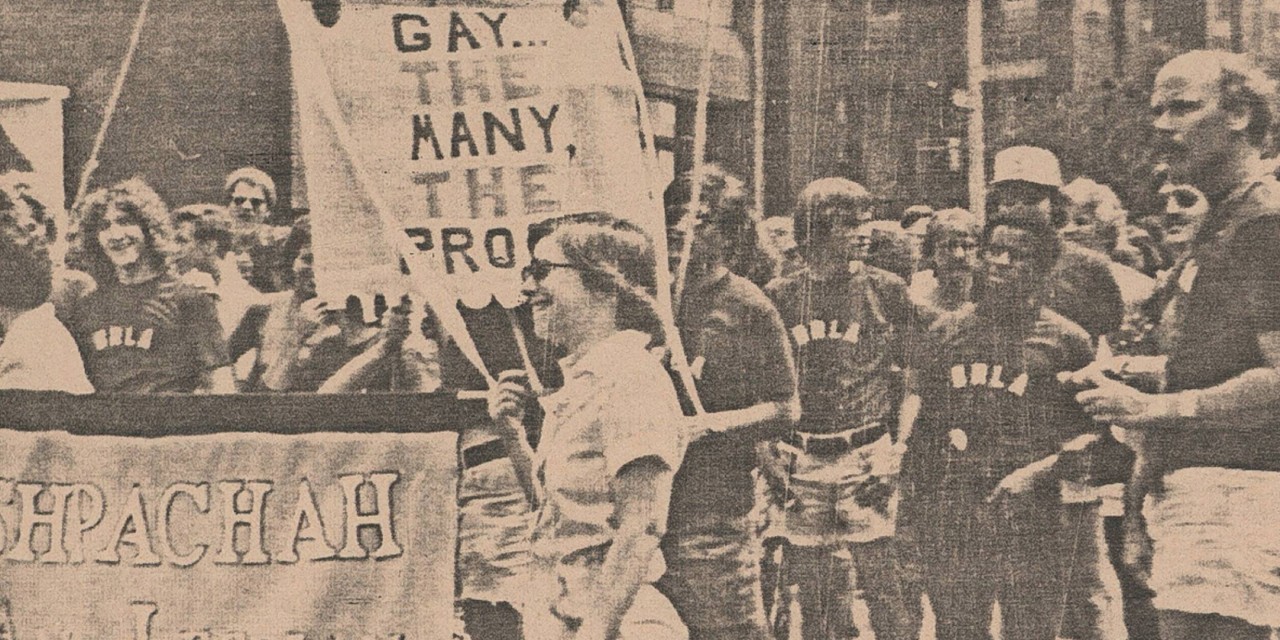

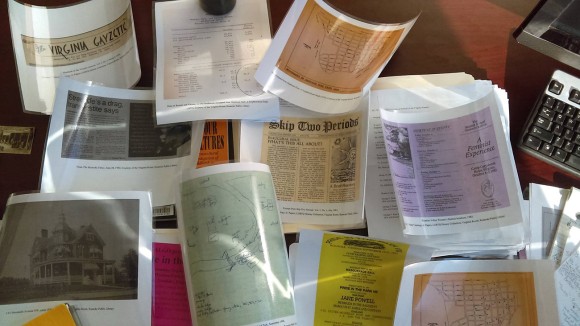

One of the project’s first initiatives involved the creation of archives, including a physical archive at the Roanoke Public Library and an online archive built with the support of Roanoke College. “People had things that they had collected for decades in their closets: old gay newspapers, flyers, posters, and memorabilia,” Rosenthal recalls. At first, the project organized events at churches, the LGBTQ+ community center, and other LGBTQ+ spaces to encourage people to bring in their personal collections. As momentum grew, people began donating materials on their own. The archive has now grown to around four archival boxes at the library. Many of the archival materials are digitized and available online, as are oral history interviews and a series of exhibitions.

One of the project’s signature events has been what they call “story circles.” The premise is simple, Rosenthal explains: “It is inviting people to come together and share their stories. There is no recording equipment on, no one taking notes.” It began at a collection event in 2016 at the oldest gay bar in Roanoke.

“We called it a reunion. We asked people who used to go to this gay bar in ‘70s, ‘80s, and ‘90s to come back. There were about 20 some people, older folks who came and just sat around in the bar talking about their memories in that place,” Rosenthal recalls. “We just sat on the outside of the circle and people shared their stories. Ultimately, we realized this is a model for a really powerful experience for these people. It’s not about capturing their stories and doing something with it, but about facilitating a space where people can feel like their lives matter or their stories matter.”

The story circle has become one of the project’s go to events, Rosenthal explains. “That is one of the most powerful, yet undocumented things that we do. It doesn’t create new evidence. It doesn’t create new archives. We don’t use it in any way, but the means is the end in creating a space where people feel valued and people feel like they can tell their story.”he