Through Study and Struggle, reading groups inside and outside of prisons build connections across the cavernous divides created and maintained by the prison industrial complex.

The idea for the study program emerged out of conversations during the 2019 Making and Unmaking Mass Incarceration conference at the University of Mississippi in Oxford, Mississippi organized by Garrett Felber. Responding to the widespread Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) raids of undocumented communities in the state during the summer leading up to the conference—and the rising death-toll within the Mississippi Department of Corrections immediately following it—the Mississippi-based political education initiative organizes and supports study groups that explore the connections between mass incarceration and immigrant detention.The program uses deep engagement with humanities sources as a tool to transcend the barriers created by the carceral state.

With its first installment in the fall of 2020, Study and Struggle offered a bilingual Spanish and English open access curriculum with discussion questions and reading materials for study groups meeting inside Mississippi prisons, outside in local Mississippi communities, and virtually across the nation. The curriculum is shaped collaboratively by a non-hierarchical team of academics, organizers, currently- and formerly-incarcerated people, and community members and made available online for use outside the bounds of the study semester. Weekly discussion topics frame the readings, prompting participants with questions such as “Why is intersectionality important for building abolitionist movements?” or “What is mutual aid? What has it looked like in your life? What can you imagine it as?” or “What is the relationship between settler colonialism and the prison industrial complex?”

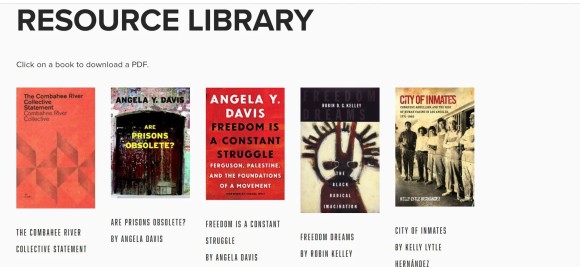

Woven throughout the curriculum are several “critical conversation” webinars supported by Haymarket Books. These conversations anticipate the month’s themes by placing the texts alongside the voices of prominent prison abolitionists and scholars such as Dean Spade, Kelly Lytle Hernández, Angela Y. Davis, and Lorgia García Peña. While bilingual transcriptions of the critical conversations are sent to inside groups, the webinars also operate as donation-based fundraisers, with collected funds from each call given to one of Study and Struggle’s organizing partners in Mississippi. In 2021, Study and Struggle adjusted the format of these conversations to put outside organizers in conversation with those inside, raising money from the events for commissary and mutual aid funds.

Funds raised from these events, mutual aid grant support from the Southern Power Fund, and other outside grants allow Study and Struggle to subsidize the participation of over 100 participants inside and outside prisons in Mississippi. Funds raised pay equal “flat” wage payments for a few organizers and cover books, photocopies, and mailings by 1977 Books, an abolitionist bookstore in Montgomery, Alabama. A significant portion of the annual budget goes toward putting money on incarcerated participants’ commissary for emergency support as well as the purchase of food, notebooks, and other study materials with the intention of supporting and cultivating group camaraderie.

For Felber, a co-organizer of Study and Struggle and current visiting fellow in American Studies at Yale University, political education is a core component of a larger ecosystem of social movements. “Study isn't instead of action, it's not standing in for it. It's not an end in itself, study is itself an action and an ongoing practice within any radical social movement.” Noting a long tradition of combining political education with mutual aid and direct action in line with the work of the Black Panther Party and the Third World Women’s Alliance, Study and Struggle organizers emphasized the collective nature of studying as a building block toward collective consciousness raising. “Study is a very collaborative, collective thing,” Felber says, “We all think different things about how we got here. We think different things about our capacities to affect change in that system. And we think different things about what we're even trying to achieve. To move forward, those things have to be sharpened and we have to figure out where those points of connection are. Study is an occasion to do all of that.” Another co-organizer of Study and Struggle, Cam Calisch, emphasizes the power of education through reading. “[T]hrough sharing these texts, it's created a lot of intimacy and shared language,” Calisch notes. “So as we're articulating strategies together, inside and outside we can reference these books that we've read.”

To emphasize community building across borders and barriers, participants on the inside and outside are encouraged to take part in a pen pal program, where students can exchange letters discussing their views on the readings and support one another. Even after the first season of the study program ended, some of the participants continued to exchange letters, a testament to how a collective approach to studying can lead to stronger interpersonal relationships, friendship, and prisoner solidarity and support.

Through anonymous surveys created by the National Humanities Alliance in collaboration with Study and Struggle and circulated to members of study group participants on the inside, respondents reflected on the positive experience of having a space to come together, discuss, and debate around issues related to incarceration and immigrant detention. “I saw it as a way to get educated and be able to educate someone else,” said one participant. On the pen pal program, another respondent noted that the correspondences “helped me to understand the issues in depth. It was the first time in life taking a look at some of the areas in society that need addressing. My pen pal’s thoughts and ideas gave me the opportunity to look at my thoughts and ideas and find a happy median from a trusted stranger.” One respondent was particularly moved by the collective effort of prison abolition, noting “at first I was skeptical about prison abolition, until I put some thought into the abolition of the death penalty in some states, and the abolition of slavery world-wide. Study and Struggle has given my family and friends a boost of encouragement by learning that there are people all over the world fighting for my release.”

Overall, Calisch notes that many participants in the Study and Struggle program have expressed how valuable the study space was for their understanding of abolition work. “The biggest takeaway was definitely people saying things like ‘we have not had a space like this before. We are learning so much about each other. And we're learning so much about how to articulate that these things that have happened to us are not our fault, that this is a part of a bigger system.’ That created intimacy with the group and relationships that didn't exist before.”

While impactful and continuing to grow in its mission and scale, the Study and Struggle initiative was met with resistance from its institutional home at the University of Mississippi (UM). Felber, who at the time of the initiative’s creation was an Assistant Professor of History at UM, received several substantial grants to be administered through the University’s foundation. Despite signing an amended memorandum of understanding regarding the project, Felber’s department chair rejected a $42,000 grant because it constituted “mostly contemporary, political activism rather than public history work.” Felber publicly criticized the rejection and his tenure-track contract was terminated. The Center for Economic Research and Social Change, which operates as an independent, nonprofit book publisher based in Chicago, offered a new fiscal home for Study and Struggle that more closely aligned with the ongoing work and mission of the program.

Though Study and Struggle’s transition from being housed under UM to being taken on by a non-profit represents a familiar trajectory for many publicly engaged projects that begin at universities, Felber sees the University of Mississippi’s resistance to the initiative as indicative of an entrenched resistance to doing horizontal publicly-engaged, political education work in academia writ large. “The way the university even thinks about what's possible within it, it becomes illegible to them once you stop seeing people in fundamentally hierarchical terms. If you see people as either students or professors that's legible to them, but the second you start talking in non-hierarchical organizing terms of like, ‘we're building this together, we're co-organizers, these people aren't just participants’ it just becomes out of their scope of possibility.” Felber notes how isolating doing public facing work can be as a result. “A lot of people find themselves in universities lost trying to do this work ... Ultimately what the university offers us are the people who are in the community that are doing this work.”

As Study and Struggle continues to grow both locally and nationally, the team is working to build out several programs that will complement the more intensive fall study curriculum. For those study groups that wanted to continue from the fall semester, the Study and Struggle team created a bridge program from January to August in 2021 that facilitated these groups in reading one book a month with discussion questions. The initiative also hopes to create a youth abolition summer camp for high school-age students, having helped to support and fund four high school students through the Mississippi-based Immigrant Alliance for Justice and Equity during the summer of 2021. At the core of this work is an understanding of study as a collective enterprise and necessary component of any transformative social change.

September, 2021