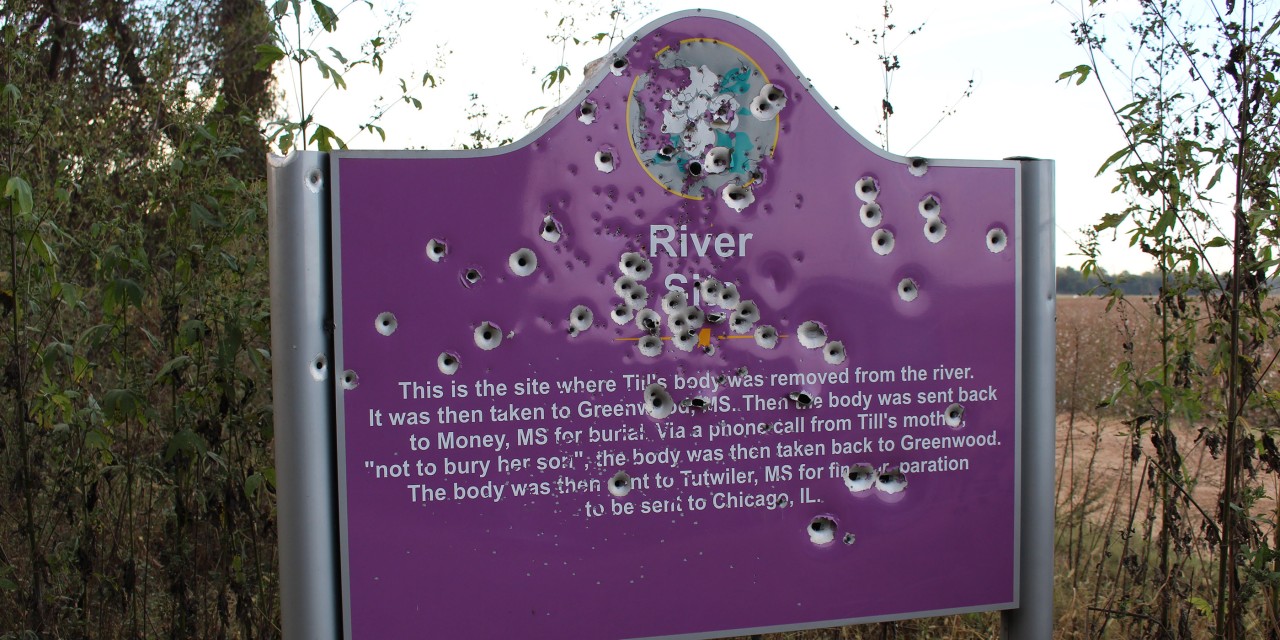

In the early morning of August 28, 1955, Emmett Till was abducted and murdered in Money, Mississippi. Plaques marking the people, places, and events surrounding the killing of the 14-year-old African American and the subsequent trial have been vandalized since their installation in 2007: sprayed with bullets, scraped of their words, and even uprooted and thrown in the nearby river. In 2014, Dave Tell of the University of Kansas and Patrick Weems of the Emmett Till Memorial Commission launched the Emmett Till Memory Project to respond to these acts of vandalism by creating digital memorials that could not be defaced.

The collaboration began after a chapter of Tell’s dissertation began to circulate among activists in the Mississippi Delta. Weems and local community organizers and historians invited Tell to the area. “It was a transformative trip for me,” Tell says—including engagement with significant people and places from the abduction and murder of Emmett Till.

“What was going on then, the big anxiety was after 50 years of silence… the state of Mississippi was finally putting up roadside markers and doing work to commemorate the memory of Emmett Till. But no sooner would they put a sign up than it would be stolen or shot with bullet holes or thrown in the river,” Tell continues. “There was this anxiety about how we can commemorate these sites in a way that’s relatively vandal proof. That was combined with another problem, that the community organizers doing the work in the Delta didn’t have the historical background to be able to tell the nuance of the story.”

Phase 1: A Prototype in Partnership with Google

While Tell was touring the Mississippi Delta, his hosts suggested creating a five-site GPS-enabled mobile app to tell Till’s story. Tell made contact with Google, which at the time owned Field Trip—an app that alerts users to sites of interests in their immediate vicinity.

“They said, we’ll do this, but we need you to have 50 sites and not 5 sites. So I went back down there and worked with Patrick Weems,” Tell explained. “Patrick and I spent two weeks driving around the Delta, talking to people, and figuring out what could be sites we could use. Lo and behold, we came up with these fifty sites. For sure, some of them are rather distant from the Till story. Including them was the cost of getting our prototype on Google.”

Phase 2: The Emmett Till Memory Project App

In August 2019, Tell and the Emmett Till Memory Project Team launched a new dedicated website and app using the National Endowment for the Humanities–funded CurateScape platform.

The app offers a more deliberately curated experience, featuring 18 rather than the initial 50 sites. This arrangement is both more manageable for users and better suited to the project’s core mission of enabling individuals to engage thoughtfully with Till’s story. “Our hope was that if people thought critically about the murder, then Till’s memory would live in their minds, instead of simply stored online,” Tell explains. “Our mechanism for encouraging people to thoughtfully engage the murder was to tell the story from the perspective of each site. For example, users standing near the courthouse would get the jury’s version of the story, while users at the site where the black press stayed would get their version of the story. These are very different stories, and that is the point.”

Reducing the number of sites from 50 to 18 makes this possible, Tell notes. “With 18 sites on the CurateScape platform, we guarantee that no matter what route a user chooses, they will be confronted with different stories of Till’s murder and, accordingly, forced to think about the murder, weigh the evidence, and decide for themselves what story they want to believe.”

CurateScape is an NEH-funded web and mobile app platform that uses Omeka to publish location-based content.

“CurateScape has been a fantastic experience,” Tell reflects. “Although it is far from free, it was far more competitive financially than other options we had been exploring. CurateScape uses a common code for all its projects. While this results in a certain aesthetic and functional similarity across projects, it also allows CurateScape to keep the costs down. We have found CurateScape to be easy to work with, their platform easy to use, and their staff responsive to the unique needs and challenges of the Emmett Till Memory Project. I recommend CurateScape without reservation.”

What’s Next for the Emmett Till Memory Project

Looking to the future, Tell plans growth in three areas. First, the Emmett Till Memory Project will add five sites in Chicago, where Till lived, selected by the Till family. Second, historical photographs will be added to the app with funding from the Institute of Museum & Library Services. Third, Tell and the project team will ensure that each site features archival documents to support the app’s narrative.

Beyond these areas of growth, Tell explained that Emmett Till Memory Project will continue to grow beyond the app. “Our agreement with CurateScape lasts for two years, so we are already thinking about next steps,” Tell explains. “Our largest goal is to use the Emmett Till Memory Project as the basis for a digital exhibit to be housed at the Emmett Till Interpretive Center in Sumner, MS... includ[ing] the app, a digital timeline on a touch-screen kiosk, Virtual Reality immersive learning experiences, and oral histories. While the exhibit would be housed at the Interpretive Center in Sumner, it could travel to any library or museum that has the technological capacity to display it."