In the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation (WUDPAC), public engagement is a critical component of graduate education. “The commitment to public engagement and outreach has always been an essential part of the education and training of conservators in our program,” explains Debra H. Norris, director of WUDPAC and chair and professor of photograph conservation. WUDPAC MA students build critical skills by working with items from the community, including participation in regular no-cost conservation clinics at the Winterthur Museum and, recently, the treatment of collections of badly damaged photographs salvaged from disasters.

In 2015 and 2016, WUDPAC students helped to stabilize and conserve fire- and flood-damaged photographs—developing skills and advancing the field of art conservation by working with real things that matter to their owners and their communities. In 2015, the group treated a collection salvaged from a deadly fire near Washington Court House, Ohio. In 2016, the group treated photographs salvaged after flash flooding in Waverly, Texas. The treatment project is a piece of a larger curriculum, which covers photography conservation from the daguerreotype to the digital print.

Recovering Damaged Photographs

“After these disasters, it’s often photographs that are recovered. Individuals are often unsure how to preserve them,” Norris says.

After catastrophic flash flooding in Wimberley, Texas, a group of archivists from Austin, Texas came in to help residents recover. The archivists collected family photographs from the wreckage for treatment at local libraries, drying them out. There was a collection of roughly 200 photographs that were particularly badly damaged, however. They came from different homes and time periods, as early as the 19th century. Unable to do more at the time, the archivists froze them for later preservation and connected with WUDPAC.

“I was confident that we could help in some way,” Norris says.

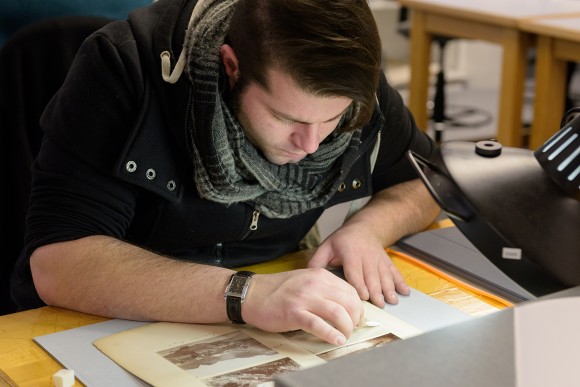

When the photos arrived in Delaware, Norris did some preliminary assessment to ensure that the conservation lab had the necessary supplies on hand. Norris then turned the photos over to the students. The group began by conducting a rigorous assessment of the collection. The students broke into teams and, working together immersively—often into the evening and on weekends—determined what needed to be done.

“The photos had been immersed in water for a long time,” Norris recalls. “There was a lot of embedded dirt, grime, and debris, image loss, distortion, and many were stuck together. When you have something wet and you leave it to dry in a plastic enclosure, there will usually be mold growth and other damage. Some of the materials were really difficult to salvage, but most of them could be salvaged.”

In addition to giving students hands-on experience, work with the fire and flood damaged photographs enabled the class to advance the field of photograph conservation. “We developed new approaches to dealing with very fragile surfaces,” Norris says. “How do you clean without damaging those surfaces? We tried different approaches to doing so. In both of these projects we strengthened the body of knowledge of how to do with objects encountered water and fire damage.”

When the class finished they passed on the photographs to the archivists working in Wimberley, Texas, who went to work returning them to their owners. Images that did not have known owners were posted on social media, reconnecting individuals and families with some their most cherished memories.

Conservation in Delaware and Around the World

This engagement fits into WUDPAC’s broader work, including outreach around the world. Norris has taught on every continent except Antarctica. Closer to home, Norris explains that the monthly conservation clinic at the Winterthur Museum is one expression of the program’s commitment to engagement.

“For decades, we have sponsored a once a month free-of-charge conservation clinic,” Norris continues. “People can bring their objects to Winterthur Museum, where they will be examined by faculty and graduate students—typically in their second year of study. Faculty and students help individuals assess the condition of these objects and determine what needs to be done to preserve them.”

It represents both an important public service and learning experience, according to Norris.

“It is really valuable to have the opportunity to examine and to speak about an object without access to extensive scientific equipment and days and days of research,” Norris notes. “Whereas our students have opportunity for in depth work, this provides an opportunity for connecting with objects in a more immediate way—and more importantly connecting with the owners who care deeply and passionately about the preservation of that object. It is certainly a service to the public, but also a wonderful training opportunity for our students.”