For humanities faculty and students, these case studies offer windows into the origins and potential benefits of publicly engaged humanities work. In communities across the country, these partnerships have taken different paths and forms. Some originate in higher education institutions, with scholars proposing collaborations to community partners. Others originate in the communities themselves. Across these diverse contexts, these four partnerships have led to the creation of new humanities knowledge and benefits for partner organizations, students, and communities. They have broadened awareness and preservation of local history, working with and for local communities to tell their stories. They are creating new and more relevant K–12 resources, drawing on the expertise of educators at all levels. They are preserving cultural heritage, creating a more representative regional history, and training new community leaders. Their work challenges academic partners to share authority and responsibility for their work, a shift that can help to both address past inequalities and injustices and to create new broader, more inclusive humanities knowledge.

An American Literary Landscape

In Putnam County, Georgia, the University of Georgia’s Willson Center for Humanities and Arts is partnering with the local K-12 school system to explore the region’s history and literary heritage through its initiative, An American Literary Landscape. The writer Alice Walker was born and raised in Putnam County, and the project explores the world in which Walker grew up through the collection and exhibition of images depicting African American life in Putnam County. The images depict the people and places that made up the world of her grandparents, her parents, and her peers. By conducting and curating oral histories using these images as prompts, An American Literary Landscape is raising awareness of the region’s rich literary and cultural heritage and establishing this heritage as an asset for its schools and the wider community. The initiative is a partnership between the Willson Center (with collaboration on campus from the UGA Libraries and the College of Education) and the Putnam County Charter School System, the Eatonton-Putnam County Historical Society, and Georgia Humanities. It has benefited from funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

An American Literary Landscape was proposed and is directed in partnership between UGA and school system staff, including Christopher Lawton and TJ Kopcha. Willson Center Executive Director Nicholas Allen explains, “The school system is the seedbed of everything. It is the community and the location, and it provides the students, teachers, parents and fellow citizens who are engaged in the program, which has had a definable positive effect on many individuals.” On-campus partners have also been crucial to An American Literary Landscape. “The College of Education has been powerful in creating structures that teachers can use in their classes for programs and assessment, in particular in shaping these practices to fit in with state requirements, and so not adding more work to an already deeply committed group,” Allen explains.

An American Literary Landscape benefited partners in ways that were both expected and unexpected, according to Allen. Students in Putnam County have benefited from a rich and locally grounded humanities experience. Their school system benefited from the curriculum that grew out of this work, as well as the positive publicity and publication opportunities for staff members. On the benefits to the campus community, Allen notes: “[W]e benefited most from being part of a diverse and engaged public humanities project that taught us a lot about planning and alliances, and also gave us a local story to tell nationally, which has had other positive effects. And our Board of Friends really gets the project, and likes that it follows our larger mission, which is to engage all our citizens in humanities partnerships.”

The work also built on—and offered perspective to—Allen’s own scholarship, which is in the literature of Ireland. “I would say… that the basis of that study prepared me to see the necessity, and the benefit, of engaging advanced thinking in literature and history in communities that desired a transformation in their self-perception,” Allen notes. “This was one basis of the Irish revolution in cultural terms and the logic applies as much to rural Georgia as it did to rural Ireland, which is to say that the imagination applied to local problems can lead to unexpected opportunities for creative minds to reshape their circumstances, if only as a dream for the future. That dream has become an unfolding reality in this project, with who knows what consequences for the economy and the community in Putnam County for the future.”

In the context of these shared benefits, Allen explains that building partnerships like this one challenge scholars to be cognizant of the legacy of past injustices. “It is a constant responsibility to be aware of this, to try and make as few missteps as possible (and some missteps perhaps are part of our own continuing education), and to attend persistently to the voices you speak with and listen to. This is all the more complicated within diverse institutional and community settings, which are themselves complex and shifting terrains.”

(Dis)placed Urban Histories

In New York City, (Dis)placed Urban Histories courses at New York University bring faculty and students together with community organizations to document the city’s changing neighborhoods. In addition to conducting research in libraries and archives, students in faculty member Rebecca Amato’s courses collaborate with community partners as they create an online archive, a physical exhibition, and walking tours. “I usually frame it as a community-engaged teaching and learning opportunity,” Amato explains. “The idea is to use history, public history, or the humanities to engage the communities with whom we’re partnering in telling their own stories and then using those stories to build common purpose and advocate for themselves and their neighbors.”

(Dis)placed Urban Histories has been taught in partnership with two organizations that focus on housing and land use issues, first Southside United HDFC (“Los Sures”) and then Women’s Housing and Economic Development Corporation (WHEDco). The two relationships have different origins, Amato notes. “In the case of Southside United HDFC, I’d heard that they had just opened up a museum space in one of the buildings they manage. This space was actually a basement storefront that they were calling ‘El Museo de Los Sures’ and they envisioned the space holding exhibitions about the history of the Latinx community in South Williamsburg. However, they were having difficulty finding people who could do this work, as well as staffing the space.” Amato saw this as an opportunity to help Los Sures realize its vision while providing a meaningful experience for her students. The project with WHEDco grew out of a conversation Amato had in the course of directing a fellowship program. As Amato discussed the possibility of placing a fellow with WHEDco, Kerry McLean, WHEDco’s vice president for community development, mentioned their ambitions for an oral history project. Amato noted, “I volunteered my class and the rest fell into place.”

In helping to set goals for their projects and determining their form, both Los Sures and WHEDCo played substantive roles in shaping the project and contributing to it. Both organizations helped identify candidates for oral history interviews. WHEDCo staff members also assisted with the logistics of the class and exhibition and sat in and talked to the (Dis)placed Urban Histories students. They were involved in all stages of the course, clarifying goals before and debriefing after each time Amato taught the course with WHEDCo.

In sharing leadership of this work, Amato stresses the importance of honoring community-based knowledge and expertise. “Working with a community partner is a process in which the scholar is not the expert, or even a researcher, so much as a student. The lessons I learn each time are really about humility. For one thing, what knowledge is and how it is kept is not always what scholars might consider legitimate. A photo album accompanied by its owner and its owner’s spoken description of the photos is a kind of knowledge-making and -keeping. Knowing which neighborhood gang you should join to secure housing for your young family in a dangerous neighborhood is another kind of knowledge. And how—or if—you record that knowledge decades later is more than an academic decision. So, ultimately, I benefited from being reminded that my knowledge is limited by a certain dominant perspective that is validated within a scholarly and, for lack of a better term, mainstream setting. But, for most people, knowledge is something very alive, very necessary for navigating everyday life, identity, and community ties. I stress all of the above in teaching.”

This can require scholars to set personal professional goals to the side and to step back, Amato says. “[A] community partnership has to be built on mutual trust and a willingness on the part of a scholar to do the hard emotional work of not being in charge.” This might mean that the course of the project is different than initially imagined, Amato continues: “The goal is to change the stakes of what it means to be a scholar and to disassemble the walls between universities and the rest of the city. To use a popular term, I do this work to decolonize knowledge-making, knowledge-keeping, and the institutions that are responsible for setting the unequal terms of what these practices mean. As a cisgender, heterosexual, middle-class, white woman in the public humanities, I cannot make these partnerships all about me. If I do, I simply perpetuate a structure of power that has long existed and needs desperately to change.”

To ensure that the project would be mutually beneficial, Amato worked with the organizations to pre-determine the goals of the project. “For Los Sures, our collaboration allowed the organization to use the museum space they had constructed in a way that was consistent with their vision for it,” Amato noted. “For WHEDco, oral history was the whole point of the collaboration and that’s precisely what my students produced. More than that, WHEDco could see the value I saw in using interviews and humanities practices, such as archiving, exhibition, and historical research, to organize their current community. Having that shared vision early on meant that we were both served by the result. As for the students, I have heard only good things about how the course helped them understand urban planning policy and gentrification better, while also introducing them to some of the people whose lives are directly affected by affordable housing construction, urban renewal, rezoning, and displacement pressure.”

Southwest Virginia LGBTQ+ History Project

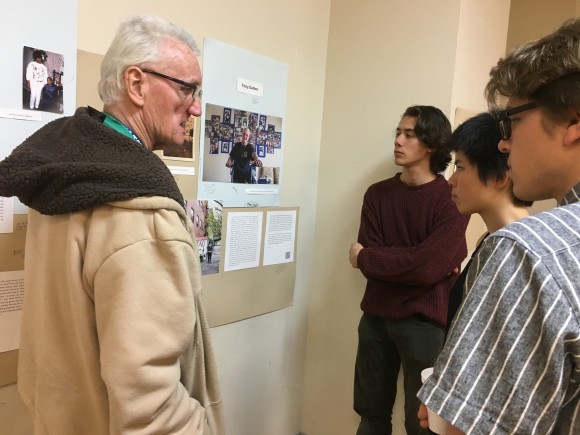

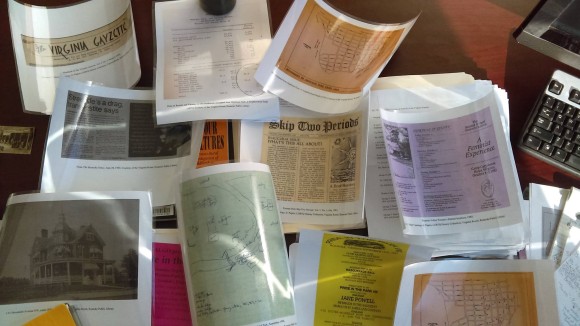

In Southwest Virginia, Gregory Samantha Rosenthal of Roanoke College is helping to lead a grassroots community-based public history initiative to tell the stories of Roanoke’s LGBTQ individuals and organizations. The Southwest Virginia LGBTQ+ History Project’s primary partners are individual community members, the Roanoke Public Library, and the Roanoke Diversity Center, an LGBTQ community organization. The project, organized through democratic monthly community meetings held at the Roanoke Public Library, has produced a digital and physical archive, collected oral histories, and offered walking tours and public programs including re-creations of LGBTQ social events from Roanoke’s past.

The project is community-led, Rosenthal says. “Since our very first meeting, we’ve invited people from the LGBTQ community to come out and they have set the agenda for what we work on,” Rosenthal notes. “We’re very focused on the ideal of democracy in doing this work and making sure that LGBTQ people are the leaders in this project and are taking the lead and are telling the stories about our community.”

There is also a broader reason for ensuring that community members take the lead. “Our project is about creating leaders and empowering leadership,” Rosenthal explains. “The goal here is to pass on skills. In fact, we have volunteers who are involved in accessioning archival collections, digitizing and putting in the metadata for digital collections, leading public walking tours, and conducting oral history interviews. These are all things I learned to do in graduate school studying public history, but they're things we have trained young LGBTQ people in the community who are not affiliated with the university to do. It provides a sense of ownership over these stories. We feel that LGBTQ history is our community’s story and it’s on us as LGBTQ people to decide how we want to tell the story.”

While individual community members guide the project, the project’s organizational partners have played important roles. The Roanoke Diversity Center’s role in the project’s history was formative, Rosenthal explains: “The Roanoke Diversity Center, in fact, hosted the initial ‘Roanoke LGBT History Project’ event that I facilitated in September 2015 at which the 18 people in attendance decided to found the Southwest Virginia LGBTQ+ History Project.” The Roanoke Public Library has provided archival expertise and labor, hosted the oral history collections produced by the project, and has been the site for most of the project’s meetings.

The formation of these partnerships with the public library was an intentional process, Rosenthal explains. “The Virginia Room, which is a regional archive within the Roanoke Public Library, was very receptive to working with us. We arranged a tour of the archives for some of our LGBTQ elders so that they could see what it’s like before deciding on going with Roanoke Public Library for our needs. Once we decided to partner with Roanoke Public Library, they have been great about amending forms to fit our needs, such as allowing for chosen names, and for varied privacy options, for both donors and oral history narrators.”

The Roanoke Diversity Center has continued to play a key role with the project. Initially, the center served as the drop-off point for materials to be archived in the Virginia Room at the Roanoke Public Library. Though these materials now go directly to the library, Rosenthal says the center continues to play a key role. It hosts the Roanoke LGBT Memorial Library, a 3,000 volume community lending library the project helped to preserve and move into the center, and continues to help manage. The Roanoke Diversity Center also provides space for the project’s community outreach events and social media support.

Each partner has benefited in concrete ways as well, Rosenthal says: “The library had no LGBTQ archival or oral history collections before our project. We have helped the Roanoke Public Library expand its collections and thus serve a broader regional audience. We have also brought a lot of LGBTQ people into the library doors for meetings and archival work.” For the Roanoke Diversity Center, the project helps bring people to the community center. “Every event we plan and hold at the Roanoke Diversity Center helps add events to their calendar,” Rosenthal notes. “We bring diverse LGBTQ people into the Roanoke Diversity Center’s doors. We manage their library…. We have provided a lot of volunteer hours to helping the Roanoke Diversity Center over the past four years. When the Roanoke Diversity Center was the sponsor of a summer camp for LGBTQ youth (which has now broken off to become its own organization), we also facilitated LGBTQ history workshops at the camp: one of our favorite programs!”

While Rosenthal emphasizes that the Southwest Virginia LGBTQ+ History Project is itself a community, rather than university-based initiative, Roanoke College and Rosenthal’s academic work have benefited from the initiative. Roanoke College students have conducted oral histories and served as paid research assistants. The project has also shaped Rosenthal’s book project on the theory and practice of doing queer public history. “[S]o many of the chapters in my book look very carefully and critically at the politics and ethics of doing just this kind of community work,” Rosenthal notes.

Great World Texts in Wisconsin

Great World Texts in Wisconsin is a project of the University of Wisconsin-Madison Center for the Humanities. In partnership with high school educators and on-campus units and curricular experts, the initiative brings literature from around the world to life in high school classrooms across the state. Focusing on different texts each year, UW–Madison scholars produce an educators’ guide and a series of on-campus programs for high school teachers and their classes. Through the adaptation and implementation of the year’s curriculum, new pedagogical and curricular engagements with literature are forged in classrooms statewide.

The project’s primary partners are the high school educators themselves, who are the engines of curricular creativity and innovation around the year’s text. In 2018-2019, the project partnered with 33 high schools. Schools have ranged from small rural charter schools to large urban Catholic schools. The program is dedicated to providing them copies of the book and a curriculum that is useful to the teachers. The schools continually shape the program through innovative pedagogy. In implementing and adapting the Great World Texts curriculum in their individual classrooms, Aaron Fai, assistant director of public humanities at the UW-Madison Center for the Humanities observes, teachers develop new curricular approaches to the study of literature. “We have been impressed over the last several years by Southern Door High School, who each year completes a group project involving the entire class—last year, in response to Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, they learned how to make beauty products from local, organic materials, and taught themselves the business skills to market and sell the finished products.”

The project also partners with the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction (DPI) and on-campus units such as the University of Wisconsin Libraries. DPI has helped reach out to high school teachers and evaluate the curriculum since the inception of the program. Aaron Fai explains, “We invite DPI to each stage of the program (fall colloquium, spring student conference, and any planning meetings) and every several years, they help us evaluate the content of the program. Most recently in 2015, they helped us evaluate our curriculum against common core standards, and ensured that we were meeting statewide educational standards.” In the past, the partnership with the UW Libraries helped to purchase books for high schools and to collect and display rare materials relating to the year’s text for high school teachers, informing their teaching. Fai notes that this partnership is growing: “We now have a librarian liaison who will help with the selection of each text, as well as find us a regional librarian who will assist with the writing of our curricular guide for that year’s text.”

Conclusions

The four examples highlighted here showcase the many ways publicly engaged humanities projects benefit both academic and community partners. (Dis)Placed Urban Histories in New York City is engaging both undergraduate students and community organizations focusing on housing and land use, informing practice with library, archival, and oral history research. An American Literary Landscape in Putnam County, Georgia preserved and provided access to a critical period in Georgia’s literary cultural history, while creating locally-grounded curricular innovations, positive publicity, and publishing opportunities for the Putnam County Charter School System. Madison’s Great World Texts in Wisconsin is helping the university serve its state by enriching literature curricula for its high school students in partnership with high school educators across the state. The Southwest Virginia LGBTQ+ History Project in Roanoke, Virginia is preserving culture, building community, and creating new resources and community spaces. It is clear that the directors of these projects value their partners, leading to processes and outcomes that recognize the contributions of all involved and that work to ensure that historical power imbalances are not reproduced.

To learn more about these and other publicly engaged humanities initiatives, explore the database below.