A Reflection on Engaging Geography in the Humanities

The Engaging Geography in the Humanities group in front of a mural in Roxbury. Image courtesy of Richard Hancuff.

During the months of June and July 2022, twenty faculty members from academic institutions throughout the United States participated in the National Endowment for the Humanities’ Summer Institute on Engaging Geography in the Humanities. Based at Northeastern University in Boston, Massachusetts, none of the participating scholars or the institute’s co-directors were trained geographers. Instead, the group was composed of sociologists, philosophers, historians, anthropologists, and literary scholars, each of us wrestling with the contours of space and place in siloed departments.

Over the course of three weeks, we attended lectures, digital workshops, panel discussions, and site visits. For the first time since graduating with doctoral degrees, we were students again. Learning from each other and collaborating with scholars at the cutting edge of digital and geohumanities, we read Henri Lefebvre’s The Production of Space alongside Cameron Blevins’ Paper Trails: The US Post and the Making of the American West. Another key contributor was the space and place of Boston. Using the city as a laboratory for exploration and the practical application of spatial theory and phenomenology, public historians and practitioners guided this experience.

Joel Mackall was the guide for our tour of the African American Heritage Trail. In his early career, Mackall managed banking affairs in Boston and Toronto. In the 1990s, he embarked on a genealogical journey to trace his family roots, which led him to Virginia. Mackall conducted extensive research and began collecting material objects related to the African American experience. These objects formed the basis of his mobile museum, where he trekked along the eastern seaboard displaying these artifacts at flea markets, schools, community centers, and prisons. A self-taught scholar, activist, and self-published author, Mackall returned to Roxbury, MA (a historically Black Diasporic community) dedicated to sharing these stories and exploring the “hidden histories” of Black Boston.

On a very hot summer morning, Mackall met our group in front of the Civil War memorial to Union Colonel Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment (an African American unit), across from the State House. He arrived with a very large binder overflowing with archival posters, playbills, images, and maps. He explained that the tour would be free-flowing and he would go “where we want to go.” For the next three hours, Mackall led us through the cobblestoned streets of Beacon Hill and over 500 years of local, national, and global history. Beginning at the State House, he showed us an image of the Sacred Cod. Hanging in the House of Representatives’ chamber, this homage to cod-fishery memorializes the fish’s role in establishing Massachusetts as an economic power since the early colonial period.

The “hidden history” of this prized vertebrate is that it was a central component of first peoples’ diet, who shared fishing techniques and preparation methods with early colonial settlers. This exchange propelled codfishing into one of the first large-scale industries established by settlers, which was globally exported. Demand grew exponentially as Europeans engaged in the trans-Atlantic slave trade, where salted cod was sent to the Carribean to feed enslaved Africans in exchange for goods such as rum, cotton, and sugar. These products were then shipped to England, Canada, and newly formed colonies. The money generated from fishing and shipbuilding established the wealth of residents living in Beacon Hill, many of whose homes are still standing today. In neighborhoods across Boston and its surrounding areas, descendants of formerly enslaved peoples still eat “salt fish” or bacalao (salted and dried cod fish) stewed in tomatoes, onions, and hot pepper served with rice or ackee, as well as fritters called bacalaitos in Spanish and accras de morue in French.

The walking tour continued with stops at the Charles Street Meeting House and homes of Maria W. Stewart, Lewis Hayden, and David Walker. At each location, Mackall revealed hidden histories of collaboration, resistance, and community. This dynamic experience ended at the African Meeting House, present-day the Museum of African American History. It was here that Mackall ended his tour with a pedagogical workshop in combining material culture and geography to prompt questions and discussions around stories kept in the margins for far too long. He implored us to return to our institutions and apply new methods of research and engaged teaching to continue making these connections between space, place, and power.

Participating in the National Endowment for the Humanities’ Summer Institute on Engaging Geography in the Humanities was a transformative experience. Reflecting on the three-week institute, I was exposed to new ways of understanding the relationship between physical and human geographies. In addition, I developed new collegial bonds with the institute participants, who challenged me to think outside disciplinary lines. Their feedback reframed key arguments for my next journal article that analyzes the impact of gentrification on migrant communities in France. Inspired by my cumulative experience in Boston, I returned to San Diego State University with new ideas for my graduate-level Public History course and made four changes to the syllabus. The first is the use of a Digital Humanities platform from one of the institute workshops. Students will have the opportunity to create their own virtual reality tours as a component of their fieldwork practicum. Scene VR allows students to develop virtual walking tours using 360° camera images and written descriptions.

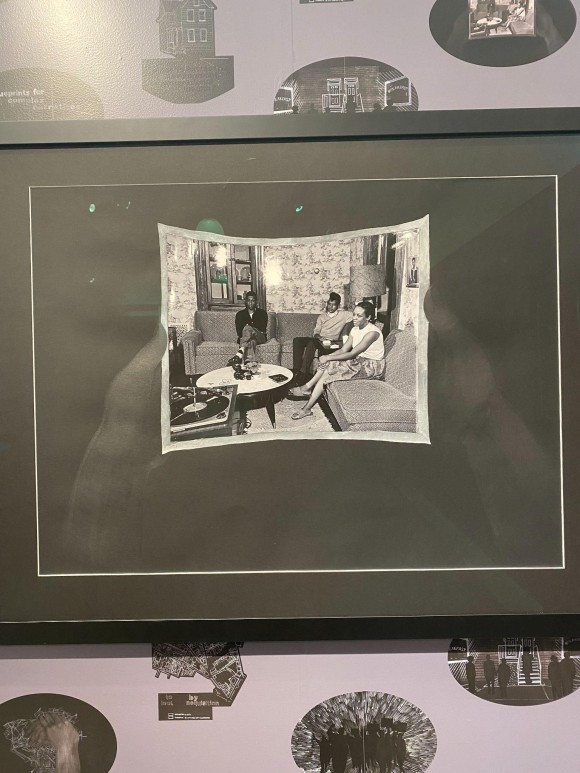

In the final week of the institute, we attended the exhibition opening of artist Alex Callender’s A Place Not Forgetting. Combining archival photographs with maps and painting, Callender navigates the Black Atlantic by raising critical questions around the legacy of colonialism, geography and the space-time continuum. Deploying this framework, I dedicated a class to examining the role of museums and the choices made by curators to contend with changing physical landscapes and its human costs using case studies from the Anacostia Community Museum. Thirdly, students were given an assignment to uncover the “hidden histories” of historical markers throughout San Diego County. They recounted stories of resilience and communities once under siege. We reviewed historic marker grant funding applications and discussed how communities remember their local history. Finally, we will welcome Joel Mackall as a guest lecturer to discuss “the politics of space.”

Kishauna Soljour is an assistant professor in the Department of Classics & Humanities and the associate director for the Center of Public and Oral History at San Diego State University. Her research and teaching interests include popular expressions of identity, the African diaspora, oral history, activism and culture.