Exploring the Carlisle Archive

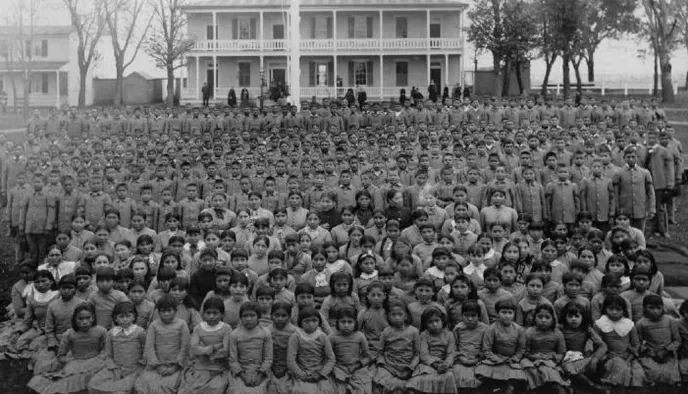

Carlisle Indian School students, circa 1890.

In her essay, “Leaving Home for Carlisle Indian School,” Berenice Levchuk (Navajo) remembers “visit[ing] the old Indian school” only to be directed to the cemetery. With recent news about hundreds of unmarked graves discovered in Canadian residential schools for Indigenous children, the reason why Levchuk was sent to the cemetery—the remaining relic of the infamous Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania—should be clear. What is often less clear are the experiences of children at schools like these, and how and why they arrived there in the first place.

When I first set out to design a public humanities research project introducing students to this important history, I hadn’t fully processed the ethics of doing so. However, this consideration quickly became a major part of the conversation. How do we honor and not oversimplify or distort the experiences of the Carlisle students, especially when the audience encountering these digitized records may be unfamiliar with the subject? Or, as Darren Lone Fight (Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara, Muscogee) put it so eloquently in an email to me, “Are we here re-enacting a second-order violence (violation) through our analytic method and purpose?”

As a teacher of ethnic American literature and composition, I am haunted by this question as I search for ways to familiarize students with the voices and experiences of marginalized groups. It is so easy to do harm, and so hard to equip readers with enough information to make ethical choices. It is also difficult to unlearn the popular dominant narratives that, for non-native people, so strongly influence the way Indigenous people are seen—or not seen. This is especially true when Hollywood has long depicted Indigenous people not only as violent and primitive, but also as existing only in a long-forgotten past.

In my Composition courses, my students and I explore these questions by reading and researching various selections from the Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center (hereby referred to as CISDRC, or the archive). The archive’s curators encourage research of Carlisle’s residents by digitally preserving student records, publications, photographs, and more. Begun by Dickinson College in 2013, the CISDRC had only been around for two years in digitized form when I offered to pilot a lesson incorporating the student records into my curriculum. I first did this through supplementary firsthand accounts of Carlisle from authors such as Zitkala-Ša (Yankton Dakota), the aforementioned Levchuk, and a documentary film entitled Warrior Women about Lakota community organizer Madonna Thunder Hawk. These texts preceded a deep dive into the archives themselves.

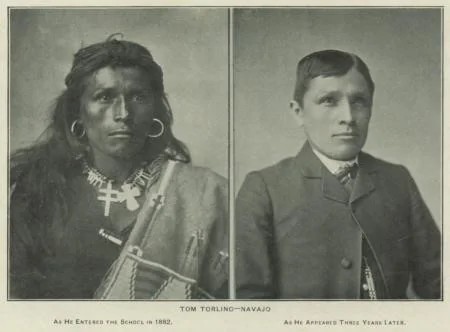

One of the most impactful ways I’ve found to begin grappling with the ethics of archival work is detailed in one of the many lesson plans provided by the CISDRC—namely, an examination of Carlisle student portraits when they first arrive compared to photographs taken much later.

Meant to prove Carlisle’s promise of “civilizing” students, the photos instead depict assimilation and cultural erasure, as evident in this famous before-and-after set of pictures of Navajo student Tom Torlino, taken three years apart.

The archives not only made historical figures like Tom Torlino more real to them, but also showed how, even with “official” records, one needs to read between the lines. Overall, my students and I benefited greatly from what Susan Wells famously identifies as the “three gifts of archival work”: namely, a resistance to closure, a loosening of resentment by productively facing the anxieties of our discipline, and finally, a reconstruction of the humanities disciplines such as rhetoric and composition in order to “rethink our political and institutional situation, [and] to find ways of teaching that are neither narrowly belletristic [or aesthetic] nor baldly vocational.” The archival medium alone can do none of these things without context, and it is one thing to inform and to educate, and quite another to make sure that we’re doing so justly and properly. With traditional research papers, I found students less inclined to consider their writing audiences or the importance of the research method themselves. Reflecting on their public humanities research work at the end of the semester, students discussed not only how their work with the CISDRC helped them think more deeply about ethical research, but also the importance of archival research issues such as reliability, privacy, and responsibility.

Describing her Black Feminist Archive, Irma McClaurin points out that archives, “even at their best […] are imperfect reflections of an imperfect world. Inequities in whose writings are collected produce inequities in whose histories become known, and the failure of vision of one generation becomes failure for the next.” Thus, in addition to providing historical context and relying on the CISDRC lesson plans, I also enlist others with more personal stakes: Namely, I rely on contemporary Indigenous voices—including memoirs such as Deborah Miranda’s (Ohlone-Costanoan Esselen) Bad Indians—for insight and instruction. One of my favorite examples is Abigail Chabitnoy’s (Aleut) poetry from How to Dress a Fish. Chabitnoy’s poems function—as Natasha Tretheway states when describing her own poetry—at “the intersections of public and personal history, cultural and historical memory, amnesia and erasure” by examining her great-grandfather’s experience and student records at Carlisle. Works such as these allow us to understand what archives can do—that is, simultaneously fill important gaps while creating others that allow room for further contemplation.

Leah Milne teaches American and postcolonial literature at the University of Indianapolis. She is the author of Novel Subjects: Authorship as Radical Self-Care in Multiethnic American Narratives (University of Iowa Press, 2021). You can find her on Twitter @DrMLovesLit.