Object Lessons: Conversations Across Generations

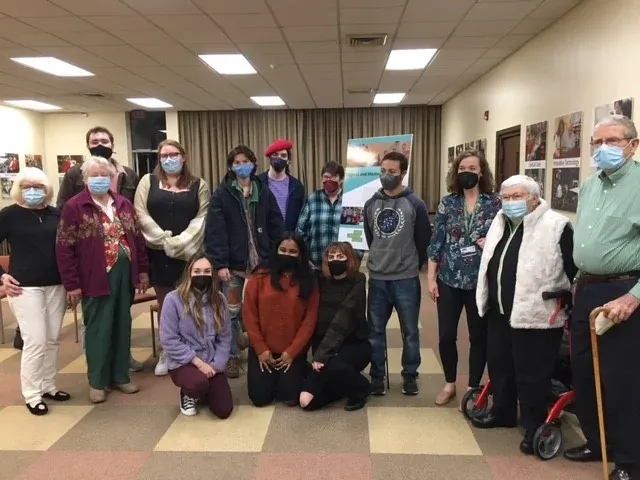

Wartburg residents and Sarah Lawrence students at the class exhibition for the Fall 2021 course “Objects and Memory.” Image courtesy of Emily C. Bloom.

This post is the first in a series of blogs by Fellows at Sarah Lawrence College, who are part of SLC’s Mellon Foundation-funded initiative Liberal Arts and the Public Good. In this post, public humanities fellow Dr. Emily C. Bloom shares her work at Sarah Lawrence and Wartburg Adult Care Community. You can read more about the Liberal Arts and the Public Good initiative here, and check out the posts from the other Fellows, Dr. Kishauna Soljour and Dr. Yeong Ran Kim.

--

My grandmother was a consummate reader. Every time I visited her at her nursing home in Long Island, she had a book in her lap. She was known by the staff as “the lady who reads.” As her dementia advanced, her experience as a reader changed. Towards the end, I’m not sure how much of the reading was just an ingrained habit—eyes that moved from left to right in a rhythmic fashion. But whatever it did for her, she stayed a reader until the very end.

I thought about my grandmother when I began a new position in fall 2021 as Public Humanities Fellow at Sarah Lawrence College and the Wartburg Adult Care Community in Mount Vernon, New York. In this three-year Mellon-funded fellowship, I serve as both faculty at Sarah Lawrence College and on the staff at Wartburg, splitting my time between both institutions. The expectation is that I will develop community-engaged courses for Sarah Lawrence undergraduates and lifelong learning opportunities for seniors at Wartburg. This work sits at the intersection between medical humanities and community engagement pedagogy, providing opportunities for students to study elder care and its challenges while also learning alongside Wartburg residents and giving both groups an opportunity to learn from each other.

Elder care is one of the pressing challenges of our time; as life expectancy increases, the elderly (those over the age of 85) are the fastest growing sector of our population and the proportion of the elderly in relation to the rest of the population is growing substantially.1 This “age wave” is a feminist issue—the majority of the elderly population are women, many of whom spent their lives caring for others without pay. It is also a social justice issue; as Silvia Federici argues, the “globalization” of care work in the 1980s and 1990s has “shifted a large amount of care-work on the shoulders of immigrant women” who are often underpaid and whose own care needs go unfulfilled.2 The question that I ask myself is, where do the humanities fit into this discussion? Can studying literature help students understand the challenges of elder care; can discussing a poem enhance the lives of our elders?

When I sat down to design courses that served these needs, I thought back to my experiences with my grandmother and I found myself often returning to poetry as a vehicle for this learning. There are barriers with poetry, for sure. Many people do not think of themselves as poetry readers. Even at 80 and 90 years old, I find many of the residents at Wartburg are still scarred from high school and college teachers who intimidated them or made them feel like they couldn’t understand poetry. But against these barriers, nothing beats the length of a sonnet for reading and discussing together or the sound of a particularly aural poem for sharing as an impromptu performance.

Wartburg serves a range of seniors from those living independently on the premises to those with dementia and Alzheimer’s who need around-the-clock care. I’ve developed different formats for these different groups. For seniors in independent living, I run a traditional college seminar where undergraduates and residents do the reading in advance and we spend the semester discussing literature together. In the fall, the course topic was “Objects and Memory” and we discussed the role of objects in preserving, stirring, or obfuscating our memories. We talked about Marcel Proust’s madeleine in Remembrance of Things Past and Samuel Beckett’s tape in Krapp’s Last Tape. The students traded stories about lost records (or video game consoles) and inherited china (or jeans). For their final project, the undergraduates interviewed the seniors about an object of significance to them and produced the recording in the form of an oral history podcast. For those in assisted living and the nursing home, instead of a traditional seminar, I’ve been holding workshops where the participants may change from day to day, but I show up every other week with an activity or a packet of poems that we read together.

Teaching at Wartburg has changed my approach to teaching literature; I’m no longer concerned with whether students understand formal structures or learn poetic terminology. I approach the poem as a room, just as the Italian word “stanza” suggests; the poem creates a space or a room where we can all meet. The actual rooms that we meet in are at Wartburg. The COVID situation has made this more challenging, but also—in some ways—more rewarding. After over a year in lockdown at Wartburg with no visitors or volunteers on site, lifelong learning programs had ground to a halt. Seniors and staff were extremely vocal with me about wanting us to meet in person, not online. To ensure everyone’s safety, we required that students taking my classes be vaccinated and boosted and provide proof of seasonal flu shots and TB tests. When we go to Wartburg, the undergraduates take a van and I’m often the driver. Meeting at Wartburg is practical, especially for seniors with mobility impairments, but it’s more than that. I’ve found that my undergraduate students are sometimes very nervous their first time going into an assisted living facility or nursing home. Some of them have experience with grandparents in similar spaces, but many do not. One student told me explicitly that she is afraid of old people. As the semester progressed, I saw tentative students grow more comfortable, leaning closer to understand seniors with speech difficulties and asking questions that showed genuine curiosity and care. At our last gathering, an impromptu dance party broke out with students and seniors bopping along to Millie Smalls’ “My Boy Lollipop.”

As my first year at Wartburg ends, I find myself more and more committed to teaching literature in this kind of multi-generational setting. As Michael Blackie and Erin Lamb write in the Journal of Medical Humanities, “texts matter, and what we do with texts in our classrooms matters.”3 I would amend this statement to say that what we do with these texts outside of the classroom matters even more.

Last week our poetry workshop met in the assisted living facility at Wartburg to read Elizabeth Bishop’s “The Art of Losing.” One of the residents was struck by Bishop’s description of losing keys—she told us how much she hates the feeling of losing her keys. Another was irritated by Bishop’s assertion that “the art of losing isn’t hard to master.” She disliked the smug presumption of the phrase. We broke into small groups and I partnered with a staff member who participated in our group—a young man who lived nearby in the Bronx. We’d been meeting every other week for six months and he hardly missed a workshop. He told me that while he was reading the poem, he thought about a friend that he had a falling out with. He wasn’t sure if this was what he was supposed to be thinking about. At the end, he said, “it’s almost like everyone looks at the poem differently. Like it’s about what we bring to it.” In this moment, he articulated exactly what I was coming to learn about public humanities pedagogy. It is about engaging different experiences in order to enhance our understanding of texts but, more importantly, our understanding of each other. The public humanities can help bring people to the same room—the same stanza—but it’s those experiences that we bring with us into the room that fill the space with meaning.

Emily C. Bloom is Public Humanities Fellow at Sarah Lawrence College and the Wartburg Adult Care Community. She is the author of The Wireless Past: Anglo-Irish Writers and the BBC, 1931-1968 (Oxford University Press, 2016), which was awarded the First Book Prize by the Modernist Studies Association. Her writing on 20th- and 21st-century British and Irish literature, the history of science and technology, and disability studies has appeared in Public Books, The Irish Times, International Yeats Studies, and Éire-Ireland, among others. Her current book, I Cannot Control Everything Forever: A Memoir of Motherhood, Science, and Art, is under contract with St. Martin's Press.