A project in Bowling Green, Kentucky, for example, is working with local Bosnian Americans to collect oral histories and artifacts and to create exhibitions that broaden understanding of their community’s experience. A project on Standing Rock Reservation in North and South Dakota is working with the tribal community to document the endangered Dakota/Lakota language.

While each project has its own particular aims, as we have collected the over 1,500 initiatives in the Humanities for All database, we have found five overarching goals toward which nearly all of these projects work:

- Informing contemporary debates;

- Amplifying community voices and histories;

- Helping individuals and communities navigate difficult experiences;

- Expanding educational access; and

- Preserving culture in times of crisis and change.

In providing descriptions of these overarching goals and examples of projects that fit into each one, this essay offers a broad view of what humanities scholars are aiming to contribute to public life. These broad categories also offer new avenues for research into the public value of the humanities. While the individual projects featured here have particular impacts—greater community understanding in Bowling Green or the preservation of Dakota/Lakota language for future generations, for example—we hope that these broad categories will serve as ways to link humanities work to broader policy conversations.

1. Informing Contemporary Debates

Publicly engaged humanities projects aim to inform contemporary debates on issues ranging from mass incarceration to environmental change to race and identity. Faculty and students bring together diverse community stakeholders, often in collaboration with community organizations, and use the humanities to start conversations. Humanities content and methodologies can productively reorient these conversations by contextualizing concerns, encouraging participants to question previous assumptions, and enriching both disciplinary and public knowledge through discussion.

The work of the Humanities Action Lab (HAL)—a Rutgers University-Newark-based coalition of universities and community organizations—showcases the importance of collaboration with local partners to bring diverse participants to the table and to use humanities content and methodologies to facilitate conversations across difference.

HAL’s States of Incarceration project, for example, facilitates conversations on mass incarceration. The project connects students and scholars with individuals impacted by incarceration in 20 cities around the country to create a traveling exhibition, web platform, and series of public dialogues exploring the roots and possible futures of mass incarceration. Associate Director Margie Weinstein explains that the project embraces humanities approaches by “bringing historical perspective to contemporary concerns to examine how the past can inform the present and understand how we got here.” States of Incarceration is student- and community-driven in all 20 locations. DePaul University, for example, co-created their contribution with an Inside-Out class at Stateville Penitentiary in Crest Hill, Illinois. As the exhibition travels to HAL chapters, it continues to spark and nuance conversations about this pressing local, national, and global issue.

Florida Water Stories—a project of the University of Florida’s Center for the Humanities and the Public Sphere (UF CHPS) and the Florida Humanities Council—is a key example of how different humanities disciplines can each enrich public discussion for people of all ages. The program brings together students and educators in two separate week-long residential summer programs on the Gainesville campus.

History helps participants in Florida Water Stories understand the roots of Florida’s contemporary relationship with water, UF CHPS Associate Director Sophia Krzys Acord explains. Religious studies, meanwhile, helps participants understand the relationships between water and sacred space—in particular how different groups including indigenous populations have valued water and conceived of the environment. Archaeology has proven to be an especially powerful way of approaching Florida’s environmental history. “Archaeologists help us to see how the issues we’re facing in Florida actually are not new,” Acord says. “People have been adapting to different kinds of climatic variations, different types of sea level rise, for millennia, and their lives provide valuable lessons that we could learn from in terms of living flexibly with water instead of trying to control it.” During their time on campus, teachers produce “action plans” to incorporate what they’ve learned into existing state-approved standards for use during the school year, broadening the conversation about environmental change for children—and their families—across Florida.

To inform public debates, publicly engaged work can also draw on humanities scholarship to encourage participants to question previous assumptions about themselves and their opinions. The DNA Discussion Project, for example, opens up conversations about race and identity using commercially available DNA ancestry tests. In doing so, this work is informed by and contributes to academic research in communication concerning the perception and articulation of racial identity.

Led by Anita Foeman and Bessie Lawton of West Chester University, participants have their DNA analyzed and then come together to discuss the questions their results sometimes raise. The project begins with a pre-survey, in which facilitators ask participants what they expect and how they would define themselves racially.

When the results of the tests are shared, the group assembles to discuss the relationship between what they expected to find and what they found and to fill out a post-survey. Two types of conversations ensue, according to Foeman. The first concerns differences between expected and actual results of the DNA test. The second explores the test’s potential impact. “How,” Foeman asks, “does this then join you to people in unexpected or expected ways?” The conversation can be personal and can uncover things that can be uncomfortable. Discomfort is not necessarily bad, though. “If you can catch people off guard with their own story, then that's like rebooting the conversation around race,” Foeman says. “Because if I don't even know what my story is, then maybe I should be a little more humble about trying to identify what box somebody else fits into.”

2. Amplifying Community Voices and Histories

Many publicly engaged humanities projects are rooted in an effort to highlight stories that are under-represented in a community’s understanding of its past and present. These projects generally depend on robust collaborations to foster narratives and identify artifacts with community members. The projects then bring a higher profile to these stories through public programming that introduces the community members’ diverse experiences and can even shift understandings of the wider community itself.

Behind the Big House, for example, works to enrich tours of antebellum houses in Holly Springs, Mississippi by incorporating the stories of enslaved people and their quarters. Behind the Big House was created in 2012 by Chelius Carter and Jenifer Eggleston of the Hugh Craft House, a historic house in Holly Springs. Jodi Skipper of the University of Mississippi began collaborating with Carter and Eggleston in the project’s first year. “I was inspired to work collaboratively with them, in an effort to remedy the paucity of sites [where] slavery [is] visible on the Mississippi landscape,” Skipper says.

Skipper has helped Carter and Eggelson highlight slave dwellings in a number of ways, including integrating Behind the Big House into University of Mississippi coursework in Southern studies and African diaspora studies by, for example, bringing students to Holly Springs to serve as docents. By bringing together students and community members, this work re-inscribes African American history into the region’s landscape through its slave dwellings, addressing a fundamental gap in Southern public history.

Efforts to amplify more contemporary voices can build off different research methodologies but with similar goals. In Bowling Green, Kentucky, for example, Brent Björkman of Western Kentucky University is collaborating with local Bosnian Americans to showcase their traditional arts and culture. The project developed out of a chance encounter between Björkman and Denis Hodžić of the Bowling Green Bosnian American community. As the two spoke, they resolved to work together to help Hodžić’s community tell its story through oral history research. In monthly meetings with partners from the university and the community, community members learned oral history methods and conducted interviews. As members of the Bosnian American community participated in the oral history project, they had the opportunity to reflect on their experience and cultural traditions in Bosnia and Kentucky. In late September 2017, the community came together to open “A Culture Carried: Bosnians in Bowling Green” at Western Kentucky University’s Kentucky Museum. The exhibition shared the community’s rich and, at times, difficult history through their arrival in Bowling Green, broadening conceptions of what it means to be a Kentuckian.

In Newark, New Jersey, Newest Americans shares A Culture Carried’s goal of broadening perceptions of a community, executing its vision through an innovative public-private “multimedia collaboratory” led by Tim Raphael of Rutgers University-Newark, Julie Winokur of Talking Eyes Media, and Ed Kashi of VII Photo.

Working across humanities and arts disciplines, the project brings together faculty, students, journalists, media-makers, and artists to tell the stories of Newark’s residents and university students who are migrants and immigrants from all around the world living together in an urban metropolis. Through classes at Rutgers University-Newark and community events and collaborations, the project creates high-quality media to celebrate Newark as a global city in which, Raphael writes, “the newest Americans from all over the world are acquiring a college education and social mobility.” With this goal, the project involves students in fellowships and courses that research, identify, and communicate the city’s stories in the archives and in the community: what Raphael calls “activating the archives.”

3. Helping Individuals and Communities Navigate Difficult Experiences

Humanities scholars and students are also engaged in a variety of efforts that use humanities pedagogies, methodologies, and content to support individuals and communities as they navigate difficult experiences. This approach has been used effectively in efforts to engage and support veterans. Another approach to supporting individuals and communities draws on the intercultural and language expertise developed through the humanities, often to connect with immigrant or refugee populations and offer them support in a variety of ways.

The efforts of English faculty from South Dakota State University are emblematic of programs for veterans that facilitate reflection and support veterans in sharing their experiences. SDSU’s Veterans' Writing Workshop/Book Club engages veterans in creative writing and guided discussions of literature and films about war that help members of the armed forces community express themselves and explore their experiences. Undergraduate aviation major and student veteran Paul McKnelly recalls that a simple conversation about an essay “turned into a conversation about life. I really recognized it right away as therapeutic to everybody that was there. It could be used as a tool for checks and balances—hey, how are you doing; how's life—it was a great experience for me.”

Other approaches to supporting individuals and communities in navigating difficult experiences involve service learning opportunities for students of world languages and cultures. At North Carolina State University, Spanish language and culture students partner with organizations that address the needs of the Hispanic community through Voluntarios Ahora en Raleigh (VOLAR). This work is mutually beneficial. For the Hispanic community, the program offers organizational support. For NCSU students, the program offers opportunities to gain professional experience and exposure to Spanish language and culture.

The University of Texas at Austin’s Refugee Student Mentor Program, meanwhile, connects university students studying Middle Eastern languages, cultures, and histories with K-12 students who are refugees from the Middle East. Roughly 70 undergraduate and graduate students serve as mentors in Austin Independent School District (AISD) schools each year, supporting existing “English as a Second Language” programs for Arabic, Persian, Pashto, and Dari speaking students and their families.

Maria Arabbo, refugee family support specialist for the Austin Independent School District, discusses the impact of the Refugee Student Mentor Program.

Working in 16 AISD schools, UT-Austin volunteers typically mentor one to three students. Following an on-campus orientation focusing on regional dialects, cultures, and how to respond to some of the typical experiences of refugees, the UT-Austin students help in any way they can. “They go according to their schedule and meet with students as mentors and tutors. Sometimes they are in classes helping students to understand assignments,” Katie Aslan of the UT-Austin Center for Middle Eastern Studies says. “They are also a social support. Occasionally, they will have lunch with students. They're just there as a friendly face, someone who understands their background and their culture. A lot of work is sitting with students and helping with specific assignments. But they also work with teachers. If a teacher has a particular task that they think their student might need help with, they might talk to one of the mentors and have them help out with that.” These experiences buttress UT-Austin students’ coursework in languages and cultures of the Middle East, exposing students to, for example, varieties of spoken Arabic and the kinds of interactions they would not get in the classroom or even by studying abroad.

4. Expanding Educational Access

A number of publicly engaged humanities projects work to broaden access to college-level humanities pedagogy, recognizing that the study of the humanities engenders lifelong benefits but is inaccessible to many. Several programs are modeled on Clemente Courses in the Humanities, which offer college-level humanities courses to people facing economic hardship. Faculty members at colleges and universities across the country tailor the Clemente model to meet particular local needs. Other projects make particular humanities disciplines more accessible to K-12 students: fields like ethics, philosophy, and anthropology are not available to the vast majority of pre-collegiate students, but access to these fields introduces them to new ways of thinking and opportunities for academic engagement. Efforts to broaden access are often designed for teachers. The University of Florida’s Florida Water Stories program discussed above helps K-14 teachers develop curricula that include religious studies, archeology, and anthropology. Other efforts involve direct engagement between scholars, college students, and K-12 students, either in the classroom or in extra-curricular activities.

The University of Notre Dame’s World Masterpieces Seminar at the South Bend Center for the Homeless is an example of a program modeled on the Clemente Course that works to address a particular community’s need. The South Bend Center program offers a version of Notre Dame’s undergraduate Great Books seminars. Focusing on the reading and discussion of great works of literature. The program creates learning opportunities for the Center’s residents to earn Notre Dame credit and to build community, self-confidence, and critical life skills that learning in the humanities endows. They are operated as interactive undergraduate seminars, a format which builds enthusiasm by encouraging residents to see themselves as students. Enrollment is open to all the Center’s homeless residents, with free on-site childcare available.

Co-founder of the program, Stephen Fallon explains that the project is driven by the conviction that the humanities create positive change. “We have a strong belief that humanities are important politically speaking. Not in terms of right or left, but in terms of enfranchising people to join the public conversation,” Fallon notes. “We believe that students who are empowered by reading classic texts will gain more of a voice and confidence to address issues in the public. We have found that students report growing in self-confidence and in the sense of belonging to a larger intellectual community.”

Operating on a similar model, numerous projects provide incarcerated and formerly incarcerated individuals access to humanities educational opportunities. For incarcerated individuals, Columbia University’s Justice-in-Education Initiative offers courses in local prisons. For formerly incarcerated individuals, Columbia also offers on-campus skills-intensive and humanities gateway courses. The cost of these courses is covered by the university. Those who complete the program are advised on ways to continue learning, at times through cost-free courses at Columbia.

The National High School Ethics Bowl, meanwhile, creates extra-curricular ethics learning opportunities for high school students who do not otherwise have access to the study of philosophy. The program, headquartered at the Parr Center for Ethics at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, brings high school students together to discuss complex ethical dilemmas after school and in regional and national competitions. In preparation for these competitions, participating high school students meet throughout the year with coaches from the community and local universities, colleges, and high schools to discuss cases produced at the Parr Center for Ethics. This programming broadens the traditional high school curriculum with the humanities, empowering students across the country to form and discuss positions on complex social problems.

5. Preserving Culture in Times of Crisis and Change

In times of crisis and change, humanities faculty and students have partnered with community members to undertake scholarship that is both integral to their disciplines and preserves culture in the U.S. and around the world. This dynamic drives a range of projects listed above, including, for example, Western Kentucky University’s work with the Bosnian-American community of Bowling Green or Jodi Skipper’s support of Behind the Big House. Partnerships with communities can often enhance preservation efforts, building trust and resources and creating channels for ongoing engagement with cultural heritage including native languages and at-risk archeological sites in conflict zones.

On the Standing Rock Reservation in North and South Dakota, Sitting Bull College is invigorating the endangered Dakota/Lakota language. In partnership with the last generation of fluent speakers, the Standing Rock Dakota/Lakota Language Project is creating original indigenous language resources by collecting traditional texts and recording conversations between elders with the goal of inspiring new Dakota/Lakota learners. The project is led by Michael Moore, Mark Holman, and elder and language instructor Gabe Black Moon, who see the project’s preservation of Dakota/Lakota language and culture as more pressing than ever. “We're losing native speakers at a very rapid rate,” Moore says. “This project is creating and preserving the knowledge of the elders—the way the elders spoke, the idioms that they used, and so on—in order to provide a base for these younger people.”

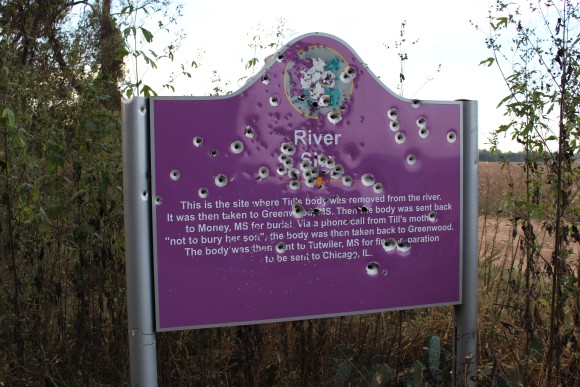

Consider also the Emmett Till Memory Project, led by Dave Tell of the University of Kansas and Patrick Weems of the Emmett Till Memorial Commission. Plaques marking the people, places, and events surrounding the murder of Emmett Till have been vandalized since their installation in 2007: sprayed with bullets, scraped of their words, and even uprooted and thrown in the nearby river. Mobilizing methodologies of historical, communication, and digital humanities research, the Emmett Till Memory Project creates digital memorials that cannot be defaced. These digital memorials are currently available through the Field Trip app. Phase two, which will help users grapple with the perspectives of different historical figures, is in development.

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives also illustrate the potential impact of the publicly engaged humanities during periods of crisis, in this case in anthropology. Working in the conflict zones of Syria, Northern Iraq, and Libya, the initiatives document, protect, and promote global awareness of at-risk cultural property including museums, libraries, and archaeological, historic, and religious sites. ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives work with stakeholders in the Middle East to protect all cultural property from both accidental and deliberate destruction as the region remains engulfed in conflict. The project team understands the protection of cultural heritage to be a matter of crucial importance, Principal Investigator Michael Danti explains. “We see what we're doing as a highly integrated and inextricable part of a larger humanitarian effort,” Danti says. “We see access to cultural heritage and cultural expression as a fundamental human right that… has been deliberately attacked and/or suppressed through the course of this conflict.”

Conclusions

Through publicly engaged research, teaching, preservation, and programming, humanities faculty and students are directing their expertise and resources to create positive change across the U.S. This mutually beneficial work aims to inform contemporary debates surrounding a range of pressing issues, amplify the voices and histories of new and long-standing American communities, support individuals and communities navigating difficult experiences, expand educational access for students in K-12 schools and beyond, and preserve cultural heritage in times of crisis and change.

The outcomes and impacts of the individual projects highlighted here are remarkable in their own right. They can be invoked as examples of what humanities faculty and students can offer particular communities and populations. They can also be invoked to shift perceptions of the humanities in contemporary higher ed institutions. They show that the benefits of the humanities in higher ed extend beyond the benefits conferred to individual students who study the humanities. Yes, humanities majors excel both personally and professionally; however, the humanities in higher ed institutions also aim to serve their broader communities every day and in times of crisis.

At the same time, we are hopeful that the overarching categories articulated here will move us toward more precise understandings of how the humanities enrich public life. To this end, this essay has worked to not only identify the goals animating the projects in Humanities for All, but also the humanities methodologies that scholars and students employ when working to achieve those goals. By articulating what the scholars themselves aim to accomplish and linking their work to these broader categories, we hope to articulate pathways for describing and documenting the impacts of humanities work. Further, we hope that these pathways will help connect this work to broader policy discussions. Better understanding the role of the publicly engaged humanities in providing educational access, for example, can intersect with broader debates in educational policy and even criminal justice reform. Similarly, the unique role of the humanities play in preserving culture in times of crisis and change makes clear that the humanities should be well-integrated into plans for disaster mitigation.

We look forward to identifying additional intersections and to refining the categories here—and perhaps adding additional ones—as we continue to collect examples of publicly engaged work.

To learn more about the projects discussed in this essay and the over 1,500 other projects in Humanities for All, explore the database below.