In order to foster and raise the profile of publicly engaged humanities work in U.S. higher education, Humanities for All offers a rich collection of examples of this work—searchable, sortable, and illustrated with select in-depth profiles. In collecting these examples, we searched existing resources that feature publicly engaged humanities work (including grants databases, conference proceedings, and publications), interviewed leaders in the field, and issued calls for participation through NHA’s members. While we will continue to collect new examples to ensure that Humanities for All captures developments in the field, to date five distinct—but very often overlapping—types of engagement have emerged:

- Outreach: scholarly programming and media for a general audience;

- Engaged public programming: public programming in which the primary objective is not to transfer knowledge but to cultivate an exchange between facilitators and participants concerning matters of shared interest;

- Engaged research: research initiatives in which higher education faculty and students partner with community members in the creation of knowledge;

- Engaged teaching: higher education instruction involving engaged research, teaching, and public programming; and

- The infrastructure of engagement: research and institutional structures that support engaged scholarship.

For faculty and students interested in embarking on or deepening their publicly engaged work, these five types offer a menu of possibilities that can be drawn on individually or combined. For advocates seeking to broaden narratives about the humanities in higher education, these five types can serve as a structure for articulating the public value of the humanities to students, parents, administrators, and elected officials. They can articulate the range of ways in which the humanities are addressing society’s pressing concerns, broadening perceptions of what humanities work can involve and impact.

Outreach

A first and well-established type of public engagement in the humanities in U.S. higher education involves outreach: the sharing of university-created knowledge with communities. Outreach activities include:

- Lectures for public audiences on and off campus;

- Websites, apps, and podcasts for public audiences;

- Exhibitions at museums, libraries, and online;

- Books, blogs, and op-eds for the public; and

- Consulting and producing reports grounded in disciplinary knowledge for media and public partners.

The dominant mode of engagement in projects included in this category is unidirectional, that is emanating from faculty members or students outward into the community. Consider, for example, Osher Lifelong Learning Institutes at colleges and universities across the U.S. These campus-based institutes offer noncredit programs for older adults, creating opportunities for outreach and enrichment involving the humanities. However, in many cases, there is an exchange of some kind. Audience members and participants are not necessarily passive consumers of content; they can often shape programming through their participation and feedback.

For faculty and students, the experience of planning and executing outreach activities can often impact their professional practice. Barry Lam, a philosopher at Vassar College, articulates the impact of his publicly engaged work—the podcast Hi-Phi Nation—on his own scholarship. Podcasting offers Lam new ways to connect with audience members. In academic philosophical writing, there is a rigor that moves the field forward. Through his podcasting work, Lam has come to see the complementary value of writing that is less regimented and perhaps more likely to have a broader appeal.

Official trailer for Hi-Phi Nation Season 1, Episode 1, “The Wishes of the Dead.” Video courtesy of Hi-Phi Nation.

Outreach can also be a component of broader programs of engaged humanities scholarship. Consider, for example, Art of the Hunt: Wyoming Traditions—an exhibition at the Wyoming State Museum that documents Wyoming’s hunting and fishing culture, arts, and lore. The exhibition itself fits within the category of outreach, but it was based on five years of fieldwork by University of Wyoming folklife specialist Andrea Graham and American studies master’s degree students, interviewing artisans including saddle makers, taxidermists, and fly tiers. In addition to incorporating these artisans’ work into the exhibition, a number also came to the museum to demonstrate their crafts and to share their stories in events supported by a grant from the Wyoming Humanities Council.

Engaged Public Programming

Engaged public programs are distinguishable from the outreach activities discussed above in that their primary objective is not to transfer knowledge but rather to cultivate an exchange between facilitators and participants concerning subjects of mutual interest. Programming of this sort has long been a key contribution of state humanities councils. For example, The Conversation Project, led by Oregon Humanities, equips Oregonians to facilitate conversations on matters of public concern.

To appreciate how this model can be implemented in higher education institutions, consider the Encounters Series at the University of Connecticut (UConn) Humanities Institute. Programs in the Encounters Series bring UConn humanities faculty into dialogue with community members about issues like citizenship and wealth inequality in the U.S. The Encounters Series is a fully collaborative and collective endeavor, produced in partnership with off-campus centers including the Hartford Public Library, the Wadsworth Atheneum, and the Amistad Center for Art & Culture. These community partners play equal roles in determining the subjects of the conversations and planning the events, in addition to building connections with the community. Each session revolves around the group analysis of a significant “text,” including, among other things, writings, images, and pieces of music. Through a structured conversation in small groups with members of the Encounters team, participants share their thoughts and assemble a list of questions they would like to ask an expert. When each table is primed with questions, the Encounters team brings in a subject-matter expert from the university or the community for a discussion based on each table’s questions.

Engaged Research

Engaged research—often referred to as community-based, participatory, or action research—involves collaboration between higher education faculty and students and community members that creates knowledge.

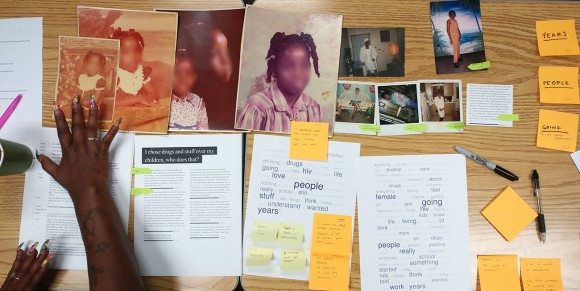

A good example of this approach is “I’m Still Surviving,” a design and oral and public history project that documents, interprets, and presents women’s experiences with HIV/AIDS in the U.S. Led by historian Jennifer Brier at the University of Illinois at Chicago and designer Matthew Wizinsky at the University of Cincinnati as a part of the History Moves initiative, the “I’m Still Surviving” project is a partnership with women living with HIV/AIDS in Brooklyn, NY, Chicago, IL, and Raleigh-Durham, NC. Almost all of these women have been part of the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS)—a longitudinal medical research project established in 1993. With “I’m Still Surviving,” the participating women become the researchers. Together with their university-based partners, they collect and analyze oral history interviews to produce books and traveling exhibitions on their experiences as women living with HIV. Through this collaborative work, “I’m Still Surviving” is broadening historical understanding of HIV/AIDS and breaking new ground in oral and public history practice.

Scribes of the Cairo Geniza represents another compelling engaged research project. The international partnership led by the University of Pennsylvania Libraries and Zooniverse mobilizes volunteer humanists to identify, decipher, and transcribe pre-modern and medieval texts in Hebrew and Arabic script from the geniza (storeroom) of the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Fustat, Egypt. These texts offer an unparalleled window into Jewish and non-Jewish cultural and commercial history in the region, especially during the 10-13th centuries. With a sample size this large, dispersed, and diverse, Samantha Blickhan of the Adler Planetarium and Zooniverse suggests that crowdsourcing presents a fruitful way forward for research and public access. “Online volunteering... offer[s] an alternative or complementary form of engagement that has many benefits,” Blickhan notes. “Online projects can reach a wider range of individuals, including those who are less able-bodied or geographically remote from the institution in which they want to volunteer and/or unable to travel. This is particularly useful for a dataset like the Geniza fragments, due to their wide range of geographic locations across institutions.”

Engaged Teaching

Engaged teaching projects integrate public engagement—whether through outreach, engaged public programming, or engaged research—into undergraduate and graduate instruction. The results can enhance curricula with project-based learning that benefits both the higher education institution and the community partners.

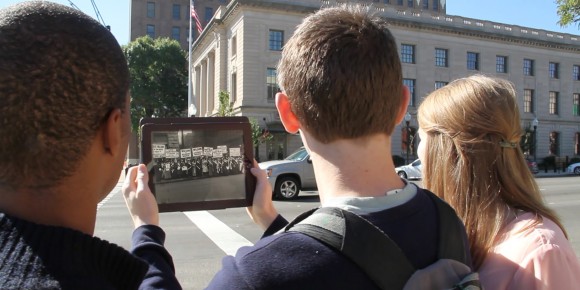

Clio—a GPS enabled app and website for sharing local history—is an example of a project that uses digital technologies to incorporate public engagement into undergraduate humanities classrooms. Illinois College’s Jenny Barker-Devine has used Clio in a first-year classroom to create entries for significant locations in Jacksonville, IL. “Clio offered an ideal entry-level platform,” Barker-Devine writes. “I wanted students to not only learn technical skills, but also to take on a local history project that would develop their research capabilities, promote civic engagement, and foster a connection with Jacksonville, the students’ home for the next four years.” The class’s ultimate impact was significant, Barker-Devine concludes: “As they honed a variety of skills, from historical research and writing to public speaking and marketing, they came to appreciate the broader applications of history outside of the classroom and as a vehicle for civic engagement.”

At California State University, Monterey Bay (CSUMB), engaged teaching is an integral part of the student experience through service learning that offers opportunities for personal, professional, and community development. Seth Pollack of CSUMB explains that the university’s service learning programs address issues of social responsibility and social justice. “We see service learning as a way to rethink the knowledge of your discipline through the lenses of service, social responsibility, and social justice,” Pollack says. Humanities students in the museum studies program and the oral history and community memory program have become directly involved in telling a more inclusive version of the region’s history through the Salinas Chinatown Oral History Project. Pollack says, “these programs have worked with the Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino immigrant communities to help build the foundation of a new Asian American museum in Salinas, which is our county seat, to be able to tell the hidden history, and the important role that these communities played in our region.” This work has impacted both students and the Chinatown community in tangible ways, deepening disciplinary knowledge through service, social responsibility, and social justice; equipping students with critical skills and experience through the humanities; and helping to revitalize the neighborhood and its residents.

Publicly engaged teaching can also prepare graduate students for a variety of career paths, as Joseph Stanhope Cialdella of the University of Michigan has noted. A powerful example of this comes from the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation (WUDPAC), where public engagement is an integral component of graduate education. Art Conservation MA students build critical skills by working with community members and their cherished items, including participating in regular no-cost conservation clinics at the Winterthur Museum and treating collections of badly damaged photographs salvaged from disasters. In 2015 and 2016, Art Conservation students helped to stabilize and conserve fire- and flood-damaged photographs—developing skills by working with real things that matter to their owners and their communities.

Infrastructure of Engagement

Colleges and universities, scholarly societies, higher education organizations, and foundations have invested in a variety of programs and institutions to support engagement activities. Humanities for All includes these efforts under the category of Infrastructure of Engagement. This infrastructure can involve:

- Funding for faculty and student engaged research, teaching, and programming;

- Recognition of engagement in policies for tenure and promotion;

- Faculty and graduate student training programs (institutes, certificates, degrees);

- Centers dedicated to engaged research, teaching, and programming;

- Event series, including lectures and other engaged public programs; and

- Conferences and consortia supporting publicly engaged scholarship;

Infrastructure can support engagement for both faculty and graduate students.

For example, a $5,000 competitive fellowship for faculty from the Center for the Humanities at the University of New Hampshire (UNH) supports work that “emphasizes sustained collaboration and partnership with community organizations, mutual respect among academic and community partners, and the recognition that knowledge and expertise are not the exclusive purview of academic practitioners.” Eleanor Harrison-Buck received such an award and was later nominated by the director of the Center for the Humanities at UNH for a Whiting Public Engagement Fellowship. The Whiting Fellowship allowed her to expand on her work with Kriol communities in Belize and to develop a collaboration with Sara Clarke-Vivier, leading to the establishment of the Crooked Tree Museum and Cultural Heritage Center.

To support engaged graduate work, the University of Michigan Rackham Graduate School created the Rackham Program in Public Scholarship. Working with graduate students in all fields, the program offers a range of professional development resources, including a summer institute on public scholarship, a yearlong series of workshops on engaged teaching, and financial support for public scholarship in the form of grants and fellowships.

Scholarly societies also play key roles in creating infrastructure to support and incentivize engagement. To list a few examples on Humanities for All, the American Philosophical Association organized an annual public philosophy op-ed contest; the American Academy of Religion collaborates with the Religious Freedom Center of the Newseum Institute to lead the Public Scholars Project, supporting scholars of religion to communicate effectively and foster religious literacy; and the Society for Biblical Literature operates Bible Odyssey—a website where scholars present historical and literary research on the Bible for a broad audience.

Five Overlapping Types of Publicly Engaged Humanities Work

While examples of each of the five types of publicly engaged humanities work reviewed in this essay are represented on Humanities for All, more than one of these types are often present in a single project. By way of conclusion, it may be helpful to discuss a project that includes all five types discussed above: Baltimore Traces courses at the University of Maryland–Baltimore County (UMBC). These publicly engaged courses bring faculty, students, and community members together to create media and public programming on Baltimore’s residents and changing neighborhoods.

Baltimore Traces courses represent an important engaged learning opportunity for UMBC students. The fall 2017 iteration of the course taught by faculty member Nicole King brought students to Baltimore’s Lexington Market soon after the city announced a $40 million plan to raze and redevelop the public market. King and her students worked with the market’s community of customers, vendors, and management to communicate news about the redevelopment and to explore their responses. They researched the market’s history and created media and programming to share with the market community, including two public history zines, a ten-minute podcast, and a public event at the end of the semester to share student research and celebrate the community’s recognition of Lexington Market. In doing so, the course included all the types of engagement listed above. First and foremost, it represents an example of engaged teaching. It involved outreach, sharing information about the market through a range of media. It involved engaged public programming, creating a humanities experience through the end-of-semester public program. It involved engaged research, including oral history research that served as the driver of the class’s work. The Baltimore Traces courses have been supported by a number of internal UMBC grants, which represent examples of the infrastructure of engagement.

For practitioners in higher education, Baltimore Traces represents a model that can inspire new or broader outreach and engaged public programming, research, and teaching. It also makes clear that institutional funding creates the infrastructure necessary to support public engagement.

For advocates, Baltimore Traces courses can help make the case for the potential impact of all five types of publicly engaged humanities work. Their engaged teaching shows how the humanities connect students with their communities and provide them with hands-on experiences. Their engaged research demonstrates that the humanities can play an essential role in preserving, understanding, and amplifying a community’s stories. Their public programming and outreach efforts make clear that the humanities have a key role to play in facilitating dialogue around issues of public concern. Finally, UMBC’s internal funding can serve as an example in advocating for similar infrastructure on other campuses.

Humanities for All works to capture the details of projects like Baltimore Traces and the voices of those involved. As Christina Kwegan, Baltimore Traces fellow and UMBC alumna, writes in a zine produced in the fall of 2017, “I am able to combine the love I have for my city with my passion to capture meaningful stories from the city’s residents and visitors. This has opened up new doors for me and given me a different perspective on parts of the city I’ve known my whole life.” Words like hers—and those of other students, project directors, and community members who have participated in publicly engaged humanities work—capture the multi-faceted benefits of these projects for all involved.

To learn more about Baltimore Traces and the over 1,500 other projects in Humanities for All, explore the database below.